DISCLAIMER: This article contains obsolete language that stems from the pathologization of realities that in no case are considered disorders by any reputable Psychology or Psychiatry institution, both at a national and international level. The language used in this article reflects the evolution of academic and health institutions throughout history and it is included here to reflect how the approach of institutions to social demands influences the categorization of the realities studied.

As is often the case with ideas that seem to be my own, it is not clear to me whether the thoughts underlying this article – and the next one that I will publish as a continuation of it – are homegrown or the result of having read about them somewhere. Probably the latter, hence why I am very grateful to all those who write about human rights and the importance of ethical practices within institutions. It has long been clear to me that being original is wildly overrated. If someone has good ideas, it is better to listen to them, internalize them and elaborate on them so that you can expand them in a way that makes sense within your own worldview and, in my case, the scientific evidence available to me. I apologize for not citing authors in these articles, but it is difficult for me to point to anyone specific. However, I would like to briefly mention Devon Price, a social psychologist who does an incredible job at educating and advocating for human rights. It may seem unexpected that I, as a Psychologist doing therapy at a clinic, would mention a Social Psychologist as an author I resort to for relevant topics about my work. However, because of my eagerness to do evidence-based work, Behavior Analysis is central in my practice because this approach, even if heavily misunderstood, is focused on the interaction between a person and their environment. Therefore, Social Psychology is perfect if I want to broaden my understanding of how our context shapes our reality.

Since it dawned on me, I periodically catch myself thinking about how the evolution of the diagnostic labels attributed to the realities of trans people is strikingly similar to that of the labels attributed to people with non-normative sexual orientations. The depathologization of non-heterosexual people is widely accepted by all institutions of psychology and medicine, but although the depathologization of trans people follows the same path, we have not yet reached the completion of that process in part due to, I believe, the fact that society has not yet finished understanding and accepting the existence of people who identify with a gender other than the one assigned at birth based on their genitalia.

The diagnoses included in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association) and other classifications are a product of their time, as they reflect the interests of society and the paradigms most accepted by psychiatrists at the time of their publication. Thus, I have decided to show the evolution of both diagnoses assigned to homosexuality (and other non-heterosexual sexual orientations) and those assigned to trans people.

Evolution of Diagnoses Associated with Homosexuality

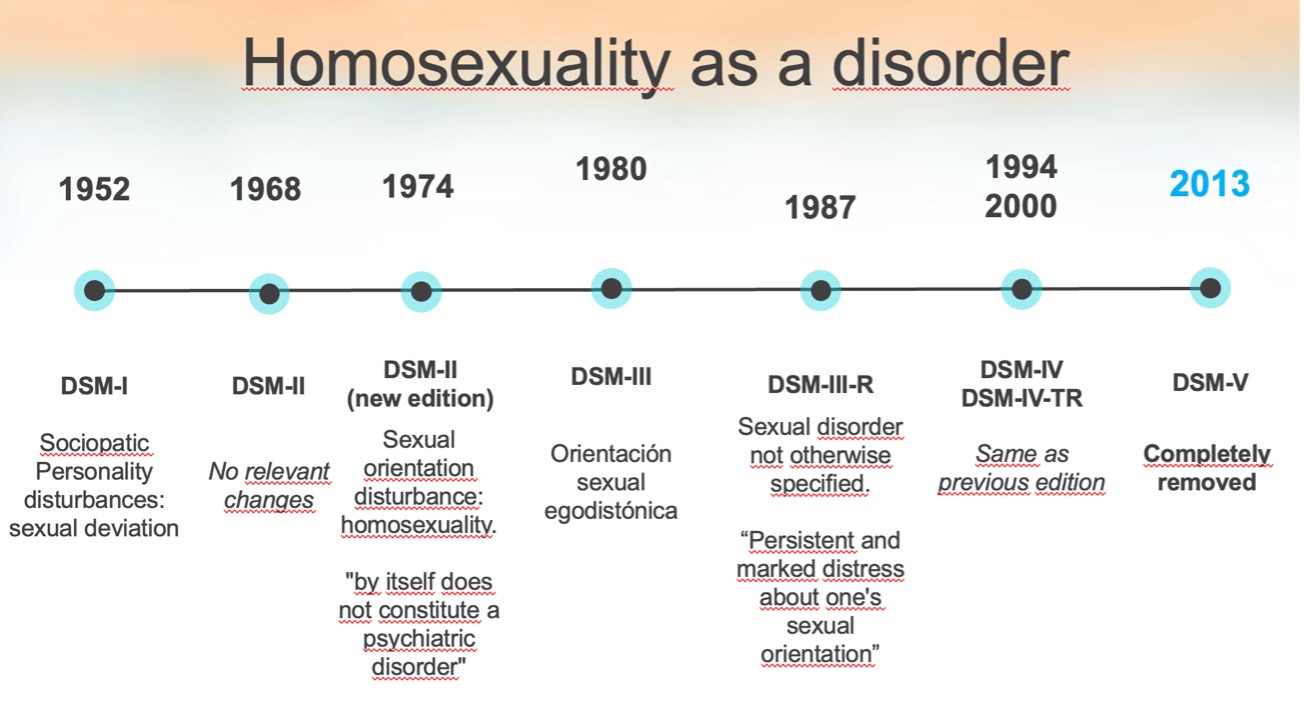

Different editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) have classified homosexuality differently, reflecting changes in the social perception of homosexuality over time.

DSM-I (1952)

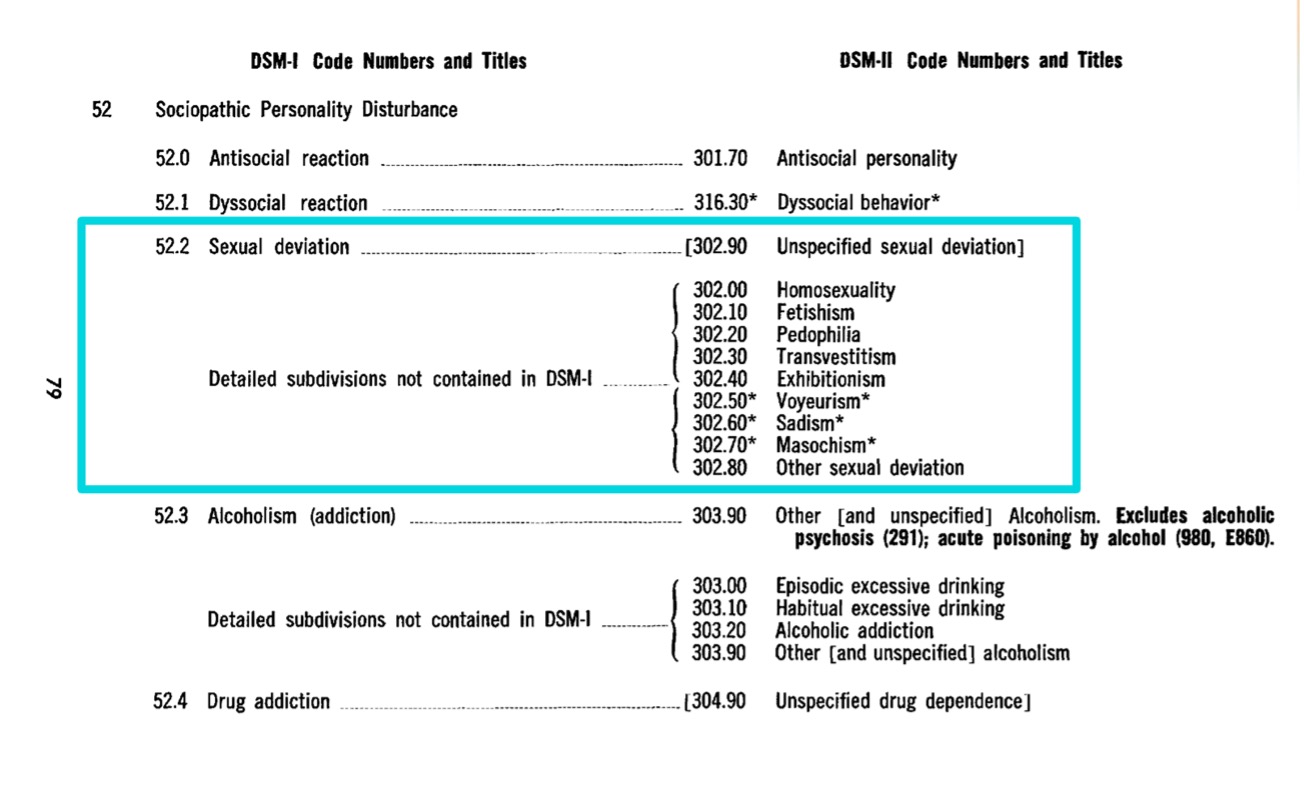

“Sociopathic Personality Disorder – Sexual Deviations”: In the first edition of the DSM, written in 1952, homosexual people are diagnosed with a “Sociopathic Personality Disorder”, within the subcategory of “Sexual Deviations”, reflecting a clear negative bias towards this population.

DSM-II (1968)

Homosexuality is still included under “Sexual Deviations”. However, this time there are a bunch of other subcategories classified as sexual deviations along with it. Thus, homosexuality appears in this edition along with other categories such as fetishism, tavestism, pedophilia and sadism, among others.

Strong criticism from society: During the 1960s and early 1970s, and due to a growing civil rights movement and pressure from LGBT activists, ordinary people and professionals begin to talk about the need for the elimination of homosexuality as a psychiatric diagnosis.

Removal of Homosexuality from DSM-II (1973):

In 1973, the Board of Directors of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) makes the decision to remove homosexuality as a mental disorder after voting on it. In its place a new category is created: “Disorders of Sexual Orientation,”. This new label does not present homosexuality as a disorder in itself, but serves as a diagnosis for homosexual people who feel conflicted about their sexual orientation.

DSM-III (1980)

In the third edition of the DSM, the former category “Disturbance of Sexual Orientation” is replaced by the new label “Egodystonic Homosexuality,” assigned to those whose sexual orientation caused them distress and who had a desire to change it.

DSM-III-R (1987)

During the DSM-III revision, Egodystonic Homosexuality was eliminated as a diagnosis. However, it is still possible to assign a diagnosis to people who experience persistent discomfort caused by their sexual orientation. For this purpose, this reality is included within “Sexual Disorders Not Otherwise Specified”, a broader category.

DSM-IV (1994)

As of the fourth edition of the manual, any allusion to homosexuality as a mental disorder is completely eliminated because sexual diversity is seen as part of normal human variation. Suffering related to one’s sexual condition no longer has a specific category, as it is understood that a specific label for people with non-normative sexual orientations can be stigmatizing and that a person can suffer for many different reasons, so it is not necessary to create so many subcategories.

Implications and conclussions

Although the chronology presented above summarizes the technical changes seen in the different editions of the manual published by the American Psychiatric Association, it must be said that these changes were clearly influenced by the harsh criticisms that the above-mentioned diagnoses received. The professionals who created these diagnostic categories were questioned, among other things, due to the poor scientific evidence provided by the theories on which they justified them.

I consider it is very important to recognize the work of those who, both inside and outside Psychology and Psychiatry institutions, helped facilitate these changes.

Thank you to those who maintain a critical attitude towards institutions and those who understand that science and its practical applications are influenced by the social realities of their time.

About the author

Jorge Jiménez Castillo is a psychologist at SINEWS, where he practices in English and Spanish. He works daily with local and international populations and has a long history of studying the reality of the LGTBIQ+ community in and out of the clinic. He works from a cognitive-behavioral approach with evidence-based interventions and believes that in order to provide quality psychological care one must be aware of the inequalities that intersect with users and explore how they intersect with each other.

Sinews MTI

Psychology, Psychiatry and Speech Therapy