What Type of E-Leader are You?

What kind of leader are you or how do you lead yourself in virtual environments? I ask you this question and not simply what kind of leader you are because at this point and after years of tsunamis of theories and talks about coaching and leadership, surely you have already identified with the charismatic leader, the authoritarian, the democratic, the inspiring ...

But suddenly, a global pandemic arrives that does not seem to end and if it does it will be after a technological sprint and having turned our work environments into virtual environments. With this new board and new rules, we are forced to redefine our leadership style, both with our teams and with ourselves.

Perhaps redefining is not the exact word but ADAPT, adapt to the new digital ecosystem, and adapt those factors of our leadership that gave us identities such as social skills, empathy, teamwork or ways of providing feedback.

An interesting bibliographic review carried out among universities in different countriesContreras & Baykal, 2020) shows how teleworking can offer numerous advantages both in terms of the well-being of employees and their productivity, but only if effective e-leadership is present. On the contrary, moving to remote work can involve numerous risks. These changes include both the adaptation of structures, trying to make them less hierarchical, and fostering trust and quality personal relationships among team members as well as a genuine interest in people's well-being.

When examining this research, I thought how applicable this is not only for leading teams but also for self-leadership, especially in self-employed workers or in those who start a new project alone. Training our cognitive flexibility, prioritizing our well-being, and maintaining contact with other people in our sector will be decisive both for the telework experience and for quality and success.

Leading remotely poses numerous challenges, but here I show you 3 of the ones that we have been able to observe the most in recent months both in fieldwork and research:

- Maintain team spirits and productivity.

- Manage uncertainty.

- Successfully management of new hires.

Obviously, the technological factor and digital skills have played a key role in adapting to teleworking, but in my experience with greater or lesser effort and with the necessary support and motivation, even the profiles with less prior exposure to technology have finished adapting.

It is therefore not surprising that we put the greatest focus on people. In the era of technology and precisely due to the automation of processes, some think that a wave of dehumanization of work will come, but it is precisely this automation that gives greater importance to personal skills and social relationships. Skills such as emotional intelligence, creativity, collaboration, and of course identity and purpose have become essential both in telecommuting and in the job market.

La Emotional intelligence is a differential variable when it comes to recognizing both how we feel and the state of mind of our team, which will allow us not only to be more empathetic leaders but also better communicators since people tend to prefer to listen to those who listen to us to those who show a coherent communication with how we feel, this makes us feel validated. A study carried out with 138 managers from 66 different organizations showed the relationship between the emotional intelligence of leaders and the creativity of their teamsRego & Sousa, 2007), a skill that for any company has become one of its main assets thanks to the need for constant innovation.

How do I do it in a virtual environment? There are multiple ways to develop emotional intelligence, from the labelling of emotions and their regulation (in this blog you will find a fantastic explanatory article written by Amanda Blanco about it), to the planning of informal meetings in small groups or there are even organizations that implement their own "mood thermometer" to be aware of the team's mood.

La Collaboration is another of the capacities that we must train in the online environment, not only because feeling part of a team's work gives us a greater identity and affinity with the organization but because, like emotional intelligence, it stimulates innovation and creativity. The University of Ludn, in Sweden, published in 2019 a study on the organizational climate and the promotion of creativity and innovation of employees, showing how environments that favor a space for entrepreneurship and in which challenges are shared are capable to foster these skills.

How do I do it in a virtual environment? The ease of convening meetings and being connected has made many people feel like they are on a constant journey from one call by zoom, teams ... to another, with an endless list of tasks and with high feelings of guilt or inefficiency in their breaks. . An alternative is to respect these breaks, to promote behaviours on the part of the leader at the end of the workday that encourages the team to enjoy other tasks or areas of their life, thus allowing ideas to emerge in moments of “unfocus”.

Finally, and concerning the purpose and identity, perhaps this is the most difficult part to adapt to the online environment, especially in cases of new incorporations or in times of high tension and uncertainty, but it is precisely that identity and purpose one of the variables that it correlates more significantly with the commitment and satisfaction of people in their jobs (even at the same level as salary and flexible hours). Therefore it is also one of the fields that have most attracted neuroscientists to research.

How do I do it in a virtual environment? Some of the ideas are the construction of the team objective and even the construction of the dynamics and the work organization that will be followed. A dynamic aimed at achieving objectives but above all COHERENT with the expressed values. For this, we can look for workspaces without sharing documents, where we can simply see each other, get to know each other, and share how we feel most comfortable working and how we each want to develop our talent during this project.

Just a few weeks ago at Sinews, we gave a group training to leaders of Everis, an organization as digital as it is people-centred, about Neuro-leadership in Virtual Environments and these needs for “reskilling” and adapting to our social relationships, to promote feedback personal and fostering group identity and purpose came to light.

Even in this training, which was online, we were able to observe that elements such as participation, emotional involvement, and looking beyond our ego were the best antidote to combat the impossibility of conducting these workshops in person.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist and Coach

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

Homesickness in Times of Pandemic

"You will never be completely at home again because part of your heart will always be elsewhere. That's is the price you pay for the richness of loving and knowing people in more than one place."

Mirim Adaney defines very well in this couple of sentences the difficulties of being an expatriate or living far away from our family and friends. All of us who have gone through this experience know how enriching and challenging it can be at the same time.

But what happens if we add to the difficulties of living away from home (often in a new culture and with a different language), the social distancing measures, and the restrictions due to COVID? Sounds complicated, doesn't it?.

It is, and it is primarily for two reasons:

- These measures are making the process of adapting to the new culture and the new place of residence very complicated, since they make it impossible or difficult to establish new social relationships and maintain regular routines such as going to the gym or attending language classes in person (places that foster the creation of new friendships and relationships as well as the establishment of routines that help us feel "at home").

- It is much more difficult, and in some cases impossible, to visit or return home to take a break, rest, and connect with our roots.

This feeling of being between two worlds, it's accentuated because, on the one hand, we cannot fully connect with the new one (establish new connections, have a satisfactory social life, go out, travel, get to know this new place, its culture, and its people) and on the other hand, we feel and are physically farther away from our roots.

In short, the process of cultural adaptation becomes much heavier and more difficult, and the impossibility of returning home is added, which produces tremendous homesickness or what we call in Spanish "MORRIÑA".

Homesickness is the feeling of sadness or grief that one feels when being away from one's homeland or loved people or places. And this very natural feeling that we experience when we are away from home is tremendously exacerbated by the uncertainty surrounding us these days due to the pandemic's consequences.

Previously, a great way to deal with this sadness was to sign up for activities that facilitated social contact, to plan the next vacation to go home, to have a definite date that allowed us to cross days off the calendar, but now, with the restrictions that accompany us, this becomes tremendously difficult and even impossible to carry out.

When we enter into this state of homesickness, we may experience challenging emotions and feelings such as sadness, fatigue, inability to concentrate, frustration, tiredness, anger... And although all of these are considered completely normal, sometimes they are very unpleasant, and the intensity can make us need some help to deal with them.

So what can we do if this happens to us?

Well, first of all, understand that what we feel is entirely normal.

As we have explained, living away from home, although it is a super enriching experience, always entails a certain degree of difficulty that is exacerbated by the current situation we are dealing with. Be patient, be aware that much of what happens is caused by the context, allow yourself to "feel sad" at times, and ask for help if necessary.

And from here, look for solutions that make us deal with this situation and symptomatology in the most positive way possible. For this, here are some tips and ideas that can help us to cope and improve our mental health in situations like this:

Find peers:

Although our idea may be to try to interact as much as possible with locals, it is always important to also have the possibility to talk to people in your same situation with whom you can share what is happening to you and what you feel. If possible and if you are from another country, if these people are from your culture and speak your language, it will help you feel closer to home. There are plenty of online groups and communities to connect people, as well as applications that are designed to make friends. Internet will be your best ally, research and find out what resources are available to you.

Stay active and pay attention to your routine:

Although it can be difficult to adapt our rhythm to the restrictions, we can always find alternatives and safely adjust and do the same activities in a COVID-free way. Try always to keep your sleeping and eating schedules as well as doing sports activities. If access to gyms is not yet an option in your city, try to practise sports outdoors or at home. Through the internet, you can also find applications and groups that can help you in this regard.

Stay connected to your roots:

Communicate with home, plan video calls with family friends, and as much as possible, try to plan activities with them. We just need a little imagination; we can cook together, eat together, go on a date, watch a movie, play online games... think about what you used to do together before and look for an alternative. Not everything has to be online communication; sometimes, sending each other letters, postcards, or photos can make us feel closer to home.

Find items that you miss:

Many times, we miss not only family and friends but also our favorite foods or products. Try to find a store that sells native products of your country or ask a family member or friend to prepare a package for you. Not only can it include your favorite cookies or sauces, but also items that make you feel close to home.

Try to connect with people in your city and make friends:

Using your hobbies for this can be a great idea. Look for activities that you enjoy and that can be done safely; you can sign up for classes or connect with people who have the same interests as you. This will gradually make you connect with new people, increasing your social circle while you enjoy and relax doing an activity.

If, after trying all this, you still have difficulties and these emotions affect and tarnish other areas of your life, remember that you can always ask for professional help.

Talking about our pain does not make it bigger; it helps us to alleviate and heal it.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist

Adults

Languages: English and Spanish

Love at a Distance

"Long-distance relationships have a 48% failure rate."

"Long-distance relationships have a 48% failure rate." Almost one in two long-distance relationships fail as a result.

It is clear that globalization and new technologies have brought us closer to the point of forming multicultural families and couples. Thus, we create more diverse, enriching, and creative environments.

But it is also true that more and more couples have long-distance relationships because they belong to different countries or because work or study circumstances make them live separately.

We all know short distance relationships (neighbouring cities or a few kilometres), medium distance (different locations in the same country or nearby countries), or long-distance (in other continents and time zones) but who was going to tell us just ago a year that we could have a long-distance relationship being so close because we are confined to our homes or that we would have to change plans and plane tickets three, four or even five times..

Of course, 2020 has left us many things, but one of them is the constant challenge to our ability to adapt and in the romantic sphere it was not going to be different.

When I was asked to write this post, my immediate response was that I was delighted to do it as a professional, since I work in couples therapy and I have learned a lot about these problems thanks to each of them. But I also have to admit that I was excited to do it from a personal point of view since I have lived for years and first-hand love at a distance.

Today I share with you the ABC of long-distance relationships or as this post of love in the times of COVID titles. I hope that after reading it you can start putting these 3 tricks into practice both in your relationship with your partner and with yourself.

Acceptance: one of the most repeated concepts in psychology, meditation, mindfulness, interpersonal relationships, and above all one of the most important tools that 2020 has left us.

Accepting means 2 things in the distance relationship:

- Accept circumstances that are not within our control, such as regulations, unexpected events, flight cancellations, or job opportunities that appear by surprise and change our plans. It hurts us to accept these changes because of the expectations that we had created of what they would be like and that we have to give up and because of the fear of their consequences. It is normal and more in a long-distance relationship that we spend time thinking about how our next meeting will be and it is also normal that we fear that if something negative does not occur, it will happen.

- Accept our difficult thoughts and emotions.This costs even more. It is many occasions to want to avoid feeling uncertainty, insecurity, lack of attention, or even wanting to avoid "waiting" is what guides our behaviour and generates tensions and conflicts.

Let's start with three tips for acceptance:

- When a change of plans or a difficult emotion comes, let's try not to react immediately, if there is no urgency, why am I going to have to respond NOW

- Let's focus on the present moment, I know this sounds very easy but we can try to do it from the capacity of adaptation trying to be creative in the couple and to look for an alternative.

- Communication without criticism.In this blog you will find another article about the horsemen of the apocalypse in the relationship and one of them is the tendency to blame the other. My recommendation is to communicate to look for alternatives but focused on the problem, avoiding criticism, and placing the responsibility or blame on the other person.

Building Bridges ”or create bridges. This is what will keep us together in the relationship and for this, here are examples of some of them:

Communication bridges: We must take care of the channels and schedules through which we are going to communicate, but also the rules and flexibility within them so as not to generate misunderstandings. Differentiating an appointment even online at a specific time which we must respect and organize as if it were in person, from communication during the day through chats or messages. So that this communication does not produce frustration, we must agree on it, reaching a common agreement in the couple.

Bridges of affection:in the same way that we take care of our plants, maintain cleaning routines at home, or maintain attention to certain details with our clients, we can do it with our relationship. These displays of affection can range from sending messages or details to other simple actions such as preparing a Spotify list depending on the mood of the other person or updating the common one with songs that are meaningful to the couple. Think that what people regret the most at the end of their lives is for not having said or shown what he felt to their loved ones, distance limits us but also offers us opportunities to create more creative and personalized bridges of affection.

Bridges of entertainment: Sharing interests, hobbies, and pleasures are according to different studies one of the key pieces in successful relationships. Although the distance does not allow us to make a route together, spend a weekend, or discover a new restaurant, technology opens the door in a simple way to take care of this bridge. Over the past few months, I have seen fantastic ideas from couples who have virtually travelled online together to destinations they would like to go to, have learned new skills, or even taught each other in different disciplines.

Discovering is always exhilarating, so why not do it together also in the distance.

Commitment is what guides our persistence, our ability to succeed in the things we value. Even in the most difficult moments, we can try to remain committed to:

- Our partners and their well-being

- The relationship as a common and constantly growing creation

- The previous bridges

- Our own emotions, to commit ourselves to accept them and develop compassion towards them, giving ourselves time, calming them, and also taking care of our own well-being.

Returning to the initial statistics ...

In order not to put our relationship at 48%, maybe you cannot change the situation but you can work on acceptance, common bridges, and commitment.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist and Coach

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

How to Take Care of my Child's Emotional Health in Times of A Pandemic

Since the beginning of times, human beings have been grouped into social entities, which has allowed them to defend themselves, reproduce, learn, and interact with the environment. Society and culture are fundamental aspects of human identity. Social interaction goes beyond mere genetic transmission, it is enriched in communication and cooperation between its members, which allows them to transmit knowledge and behaviors through learning. This is how culture is formed.

Culturally, social interaction occurs under:

- A close physical contact,

- Dates to go to the movies, eat or exercise;

- Birthdays and Holidays are highly celebrated surrounded by a ton of people

- Big parties to celebrate weddings, Christmas or holidays traditions passed from generation to generation.

All of them have in common the accumulation of people in closed or open spaces, with close proximity interactions.

However, everything has change since March 2020, when to prevent the spread of COVID-19 we had to build a wall around us, distancing ourselves from everyone. For us adults, it has not been easy to adapt to the new restrictions of distancing ourselves from all those around us. Even understanding the implications, it is difficult for us to get out of a lifetime habit of social interaction, in order to acquire new habits adapted to our current needs. If it has been extremely difficult for us ...

Can you imagine how difficult it has been for teenagers and children?

For adolescents, their main references come from social interaction with their peers in a vital moment where they seek to become independent from their parents and part of the group. It is typical at their age to constantly seek the approval of others, wanting to go out with them and building new experiences, or starting new relationships. For children who naturally seek physical contact through hugs, kisses or even during playtime (with games like tag); it is not easy to explain to them that they must keep their distance from their peers, cannot go to visiting grandparents or is forbidden to touch anything.

Social isolation is a high risk for developing mental health conditions, being loneliness and despair symptoms that could be highlighted by de social distancing. These feelings maintained for long periods of time can lead to the appearance of serious mental disorders in children and adolescents such as depression or anxiety. In a study conducted by Dr. Maria Loades, from the Department of Psychology at the University of Bath, she indicates that the implications of loneliness caused by confinement during COVID-19 will not be measurable until the following ten to twenty years. However, she confirms that it is the prolongation of lockdown, and therefore loneliness, rather than the intensity of it, that usually has the greatest impact on the appearance of depression in children and adolescents.

Confinement has had positive and negative consequences, despite the fact that most of the studies focus on the possible negative repercussions that social isolation may have; qualitative studies indicate that family time has increased, thus strengthening the bond between family members. An emphasis has been placed on interactions with pets and self-care activities that contribute to coping with the psychological consequences of the pandemic. Although we consider that we cannot do anything to compensate for self-imposed social isolation, the truth is that nowadays, as opposed to a hundred years ago when the last pandemic was registered; society has created digital communication mechanisms that allow us to bring together all those who are far away.

To help our children deal with the overwhelming feeling of loneliness, it is essential to do four things:

- Talk with your children, either through a conversation or with using the little one’s graphic tools; we must open a wide channel for communication to create an environment of emotional safety so that our children can express what they are feeling. This gives them the opportunity to externalize those deep feelings and look for possible solutions to deal with those emotions.

- Being aware of our own emotions, this allows us to act instead of reacting as a consequence. As parents, we cannot ask our children to learn how to deal with their emotions if we do not know how to deal with them ourselves. The first step is to identify the emotion we are feeling; then we must understand why we are feeling it; to finally find a way to deal with them. This practice will allow us to re-direct our emotions without affecting those we love the most.

- Maintaining a routine, schedules and routines provide structure and stability to the daily life; allowing us to establish specific times to work, eat or rest. Maintaining habits that accompany our routine such as dressing, bathing, brushing our teeth, eating on time or sleeping, help our body to maintain their biological rhythm and therefore promote our emotional balance.

- Maintaining good sleep habits, our body needs a recovery period after daily energy expenditure. During this period of time, we give our brain a break, so that it can regenerate itself. By emptying our minds, by resting, we can use it again the next day at their full potential. That is why it is important to take care of our sleep habits and the rituals that accompany it. The alteration of those habits can lead to attention problems, mood swings, decreasing memory, among others.

Now, once we know the four fundamental aspects that we must keep in order to maintain good mental health in balance, we cannot forget that this does not replace social contact in the least. For this reason, we must be creative when coming up with strategies that will help us battling this isolation with our children and adolescents.

Here are some suggestions that you can do with your children:

- Schedule physical activity with your children indoors our outdoors. They can practice Yoga that contributes to relaxation, or a Zumba class to exercise, or take a walk into the forest to breathe fresh air and change their environment.

- Play with your children, discover their interests preferably away from the screens or consoles, but that are fitting for their age. Playtime, especially in young children, develops their communication and social interaction skills. In adolescents they allow them to build memories with their parents around playful and stimulating moments. Likewise, through playtime creativity and problem solving are highly stimulated, which is a fundamental part of human development.

- Organize playdates with their classmates where children can interact with their peers through the screen. This will allow them to have a fun time in the company of those who are further away from them at this time.

- Plan a meal with grandparents or extended family, thanks to technology we can connect through our screens to have lunch or dinner with the family we cannot see physically. Having a previous agreement with them to cook the same meal and share a moment with them around the dinner table, even though it is through a screen.

- Limit the use of screens , especially if they are taking online classes. The use of screens is highly addictive and leads to the appearance of mental health problems. It is important not to exceed that daily limit, especially in teenagers it should not exceed a maximum of two hours daily (one hour when they are in online classes).

- Maintain a positive attitude, despite the difficulties we should teach our children to build resilience. It is imperative to limit the access that our children have to the news which generates uncertainty and anxiety in ourselves and furthermore in them. Also, it is helpful to encourage the occurrence of moments that promote good humor and joy at home; Starting a tickling war, creating a comedy time, where everyone has to tell a joke, or sing along on an improvised karaoke. Humor is essential to maintain a positive attitude, and to transmit it to our children.

- Express how much you care to your loved ones por ellos; sometimes we take for granted that our loved ones know how important they are to us. However, at times like this, it is worth reminding them and even thanking them for the role they play in our lives.

- Encourage your teenagers to learn a new skill in the company of their friends, they can work on a common project and share their impressions about learning this new skill or hobby. They can learn to draw with watercolor, to make cartoons, to knit; there are multiple options available where they can share the learning sources and strengthen the skill they want to learn, interacting with their peers.

- Act as a role model for your children; Our kids tend copy everything we do, especially the little ones. For that reason, it is essential for us to be an example for our children. Either in the quantity of time we use our screen, or following our daily routines or how we cope with our emotions; if we set a good example, this contributes directly to the well-being of our children.

Now that we have given you some strategies to deal with social isolation, choose one and get ready to do it, you will see that you will feel better afterwards. Remember to live one moment at time, making the most of it.

References:

Impact of children’s loneliness today could manifest in depression for years to come.

Recovered from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/05/200531200333.htm

How to maintain our relationships while in isolation.

Recovered from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/es/blog/como-mantener-nuestras-relaciones-mientras-estamos-en-aislamiento

Coronavirus: how to help children through isolation and lockdown.

Recovered at: https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-how-to-help-children-through-isolation-and-lockdown-133990

Sinews MTI

Psychology, Psychiatry and Speech Therapy

Psychological trauma and its consequences

What ‘s trauma?

According to the World Health Organization, trauma occurs when: The person has been exposed to a stressful event or situation (both brief and prolonged) of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature, which could cause profound discomfort in almost everyone (W.H.O.: ICD-10).

Trauma is a psychological reaction, following a negative and highly stressful event that appears unexpectedly and uncontrollably. By compromising the physical or psychological integrity of the person who suffers it, and being unable to cope with it, it creates a very intense discomfort in him/her.

The high psychological impact of traumatic events occurs due to the intensity of the event along with the absence of adequate psychological responses to cope with something unknown and unexpected.

To consider an event as traumatic it has to be of a negative character, unexpected and sudden.

A large part of the individuals who face a traumatic situation suffer psychological consequences afterwards, which can be acute or chronic. In the first post-traumatic moments there are symptoms that can be considered normal and very often, these symptoms remit spontaneously, but sometimes the consequences last in time or increase affecting mental health.

Symptoms associated with trauma

Once the initial shock is overcome, responses to a traumatic event may vary. The most common responses are:

- Flashbacks and nightmares.

- Anxiety and constant nervousness.

- Anger.

- Denial of the event.

- Changes in thought patterns.

- Increased difficulty concentrating.

- Avoidance behaviors towards memories of the event.

- Intense fear of a recurrence of the traumatic event, especially on anniversaries of the event or when returning to the site of the original event.

- Withdrawal and isolation in daily activities.

- Decline in general health or worsening of an existing illness.

- Changes in mood.

- Dissociation.

- Irritability and sudden mood changes.

- Physical symptomatology of stress, such as sweating, headache and nausea.

- Sleep disturbance or inability to sleep (insomnia).

For the most part, those affected will not develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety or depressive disorders or dissociative identity disorder, but normal manifestations of post-traumatic syndrome, even in situations of high psychological impact.

Traumatic disorders

After exposure to a traumatic or stressful event, severe psychological reactions may develop, leading to one of the disorders related to trauma and stress.

The diagnoses included in this category of disorders are:

PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder)

Probably the most common and studied, with a prevalence of 1-4% of the population. It is especially common in people with professions that involve a risk of exposure to traumatic events (police, health, military…). Symptoms such as persistent and recurrent nightmares and insomnia, flashbacks, isolation and high reactivity (aggressiveness, hypervigilance…), irrational fears, derealization (feeling that the world is not real) and depersonalization (feeling like an external observer of oneself) and dazedness are common.

ASD (acute stress disorder)

It is characterized by PTSD-like symptoms that occur after the traumatic event. Such symptoms may last from two days to 4 weeks after the traumatic event. What differentiates it most from PTSD is that the symptoms must appear almost immediately after the event.

Adjustment disorder

Symptomatology appears after a clear and definite traumatic event, within three months of onset, but cannot be classified as PTSD. There is intense distress disproportionate to the severity or intensity of the stressor and significant impairment in normal functioning. Distress manifests with decreased work or school performance, changes in social relationships, complications in an existing illness, problems in a partner or family, and financial difficulties.

Reactive attachment disorder (RAD) (diagnosed only in children)

It is characterized by a distortion and lack of development in the ability to relate socially. Common symptoms include sadness or fearful reactions for no apparent reason, emotionally poor reactions to others, episodes of high irritability, and limited expression of positive affect.

Disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED) (diagnosed only in children)

Appears a lack of selectivity to attachment figures of choice, being overly familiar with unfamiliar people and seeking affectionate contact outside the close social circle

Other specified disorder related to trauma and stress

Symptomatology characteristic of trauma- and stress-related disorders appears, causing significant distress and impairment in all areas, but criteria for any of the above diagnoses are not met. In this case, it is specified which other disorder might be influencing the symptomatology

Trauma and stress-related disorder not specified

The same as the previous disorder, but without specifying any other disorder.

There are several factors that can make traumatic experiences more negative. On the one hand, factors associated with the person him/herself such as the way he/she perceives and experiences the situation, resilience or mental health history. On the other hand, there are the factors associated with the situation itself: human and material losses, extension in time or chronicity, age at which it begins (in case of abuse). Finally, factors associated with the place where the event occurs; the presence of social support, the existence of preventive measures, the community culture itself, or the existing mental health care in that society.

Trauma in childhood

Considering that during childhood a child is dependent on his or her caregivers, any abusive or neglectful behavior can have a traumatic effect, being experienced as a threat to his or her own integrity.

In addition, in childhood it is common for mistreatment to be continuous, being a chronic situation for them. It is important to highlight that abandonment is another form of maltreatment, being as psychologically harmful as physical or sexual abuse.

Consequences of childhood trauma: When to seek professional help?

The reactions shown by children and adolescents who have been exposed to traumatic events can be summarized as:

- Development of new fears.

- Separation anxiety (especially in young children).

- Sleep disturbances.

- Nightmares.

- Sadness.

- Loss of interest in normal activities.

- Decreased concentration.

- Deterioration of school work.

- Anger.

- Somatic complaints.

- Irritability.

The functioning in the family, group of friends or school can be affected by these symptoms, putting at risk the mental stability of the youngest.

Dissociative disorders: response to chronic trauma

What is dissociation?

The term dissociation refers to a disconnection between mind and body; a disruption in the way the mind handles information. You may feel disconnected from your feelings, thoughts, memories and the environment around you and it can affect your sense of identity and perception of time.

Dissociation is a human defense mechanism against trauma, which allows us to blur and even eliminate experiences that are too painful to assimilate, especially when we are children and we are developing. Thus, in the face of abuse or maltreatment (especially in childhood and adolescence), dissociative symptoms are a lifesaver for many victims; the problem is that this reaction, in principle adaptive, becomes dysfunctional very quickly, affecting the mental health of the victims.

Dissociative symptoms

Dissociative symptoms are divided into three blocks: amnesia, derealization/depersonalization and confusion/alteration of identity (Steinberg, 1995).

Amnesia serves the function of allowing the patient to go on with life by selectively forgetting the distressing situation and intolerable emotion; in Dissociative Identity Disorder for example, the parts dealing with everyday life situations usually present amnesia for previous traumas.

Depersonalization disconnects the body from consciousness so that the individual can detach the traumatic experience from his or her own emotions; often when there is severe trauma we do not perceive the emotional part of the experience to defend ourselves against the degree of emotional arousal it provokes.

The alteration of identity alternates one mental state with another without creating a meta-consciousness that encompasses both.

Dissociative disorders

Dissociative disorders include several syndromes with the common core of an alteration in consciousness that affects both identity and memory:

- Dissociative amnesia, in which patients lose autobiographical memory of certain events, usually events of a traumatic or stressful nature.

- Dissociative Fugue, in which amnesia covers all (or at least a very large part) of the patient’s life and is accompanied by loss of personal identity and in many cases a physical relocation (hence the name). Dissociative amnesia can be diagnosed with or without dissociative fugue.

- Dissociative identity disorder or DID (formerly multiple personality disorder), in which the patient appears to possess and manifest two or more identities (a «host» personality and one or more «alter egos» ) that alternate control over conscious experience, thought and action and are usually separated by some degree of amnesia.

- Depersonalization disorder, in which patients feel that they have changed in some way or are somehow no longer real.

- Dissociative disorders not otherwise specified, in which the patient manifests some dissociative symptoms to some degree but falls short of qualifying for a diagnosis of the above.

Although the effects of trauma can impact areas of functioning that seem remote from the trauma, considering trauma as the primary causal influence of symptoms can help empower individuals to heal themselves with support, and validation in a safe environment.

Sinews MTI

Psychology, Psychiatry and Speech Therapy

The Four Horsemen Romantic Relationships and How to Manage Them

When does love end and become friendship?

Is there a time limit or happily ever after?

Why do some couples seem unaffected by the passage of time?

Why do other people repeat the same patterns in different relationships?

These topics are probably nothing new; most of us have discussed the secrets and obstacles of dating relationships on multiple occasions.

It is not surprising that it is one of the topics with the highest demand within psychology sessions or that it is something that worries us and in which we want to work and learn more.

We are social beings and dependent on the group (even for our survival) and probably due to the way we have articulated our relationships throughout the history of humanity, the romantic relationship is the chosen group in which we spend the most hours and in which that more projects we share.

These topics are probably nothing new; most of us have discussed the secrets and obstacles of dating relationships on multiple occasions.

It is not surprising that it is one of the topics with the highest demand within psychology sessions or that it is something that worries us and in which we want to work and learn more.

We are social beings and dependent on the group (even for our survival) and probably due to the way we have articulated our relationships throughout the history of humanity, the romantic relationship is the chosen group in which we spend the most hours and in which that more projects we share.

Studies that try to discover which are the variables related to greater happiness, well-being, and even longevity have shown that, above aspects such as economic, labor, or social class, what most influences our subjective well-being are the relationships we have with other people and more specifically with close family.

How can we not worry about our romantic relationships then? How not to try to learn more about building and maintaining a healthy, exciting, and long-lasting relationship? But above all, how can one not be aware of difficulties and learn to navigate them?

Thanks to advances in fields such as neuroscience, today we know that our brain behaves similarly when it "falls in love" as it does in addictions, we also know that we tend to positively value everything familiar to us and that after a rupture we experience physiological processes similar to those we feel in a grieving process.

For this and many other reasons, it is clear that romantic relationships and, above all, their well-being within them, is more complicated than we thought, from the beginning of the relationship to its maintenance over time.

As a therapist, I consider it fair and fundamental that we recognize and stop trivializing these difficulties since each relationship experiences them, and normalizing them is the first step to get rid of that feeling of "what is the problem with me?" and continue to evolve. This is the main objective of this article, to raise awareness and show common obstacles in couples from current scientific knowledge.

In the classes that I teach in Personality and Individual Differences, we usually talk about the relationship between personality traits, the duration of the relationship, and emotional and sexual well-being. Different studies and meta-analyses have shown aspects such as extraversion (due to the ability to communicate love and needs), openness to experience (which leads us to try new things and learn), awareness, and perseverance (for orientation to long-term goals) positively correlate with maintaining a stable and lasting relationship and with perceived happiness within it.

But we must not forget that all these behavior patterns can be trained and also that they are only correlations, that is, we do not know what was before if the chicken or the egg. Do we show ourselves in the most communicative questionnaires, open to experience, and focused on having a healthy and positive relationship, or are these variables the ones that make us have a satisfactory relationship?

Going deeper into what we know in the field of science as possible keys to a happy couple, we know that at first, we worked on the idea of “Quid Pro Quo”, that is, those people who had a sense of justice in their relationships were better able to last over time than those who did not feel that way.

But thanks to the advances in research and studies such as those of John and Julie Gottman (couples therapists, professors, and researchers at the University of Texas), we know that this need for "equality and justice" only appears in couples when they are already They find themselves going through bad times when they are in a state of alert due to not being comfortable in the relationship.

The Gottman method has shown high efficacy in couples therapy, probably because it approaches the relationship holistically, it focuses on the joint-life history, but also takes into account the learning and personality patterns of each of the members of the couple. Likewise, this method works on behavior, but without neglecting emotional regulation and patterns of thought and interpretation.

What we call the four horsemen of the apocalypse in a romantic relationship have thus been identified, these being the following:

- Criticism:An attitude of criticism and centered on blaming the other member of the couple for every little detail or problem, accusing their behavior, personality traits, or aspects of their family and/or life history.

- Defensiveness:The tendency not to assume responsibility and to be defensive in the face of possible criticism (which is usually perceived as an attack on my person and not as a behavior to modify). This attitude is closely linked to criticism since in addition to blaming the circumstances, the easiest way for the couple to defend themselves is usually to put the responsibility on the other.

- Contempt:A pattern of behavior both behavioral and verbal that delegitimizes or devalues aspects of the other member of the relationship.

- “Stone-walling” : The tendency not to establish communicationnot to deal with problems, and / or turn away from them, which in many relationships is perceived by the other member of the couple like turning your back on that person or the relationship.

Obviously, these 4 riders do not appear simultaneously in all couple problems, but one of them is usually found playing a leading role in the conflict.

It is right here where we find one of the main keys to understand and start working in a positive relationship. We know that the difference between a happy and satisfied couple and another that is not satisfied is not the number of conflicts that appear but their handling since we are capable of making a small conflict a big problem if we let any of these four horsemen between in Game.

But, now that we know a little more about scientific studies, about the evidence, and about these four attitudes as protagonists in romantic problems, what can we do with all this? How do I put it into practice?

- Real consciousness:As obvious as it may seem, it is as obvious as it is useful. We must cultivate awareness and try to identify these four horsemen, not only now when reading this article but in our day-to-day relationship. It is important to pause the conflict or before it begins and see if one of these riders is taking the helm and navigating the problem.

- Time out:Especially due to the difficulty of the previous point, since when anger, anger, or sadness are very active, it is more difficult for us to become aware and think more coldly.

Something that we can try to practice is to take time out (it can be to take a walk, go to another room ...) trying to perceive that the problem does not have to be solved NOW and above all that it will not do it if we do not handle it rationally. In many couples, this time out is a source of conflict since there are those who “need” to resolve or conclude immediately. It is therefore important that this technique is consensual and is not interpreted as an estrangement but as an individual space to reflect and then work together again in the relationship. - Emotional regulation:In the same way that we work on managing emotions in the couple, we must do it individually, first being aware of our emotional handicaps (which we all have) and then applying different psychological techniques such as cognitive restructuring, relaxation, acceptance, and subsequent distancing from emotion through mindfulness, self-compassion...

- Focus on common goals:Focus attention and behavior on common goals, nothing transcendental in principle, go from less to more, from sharing time together focused on a common interest (a walk, visit, series, talk about a book ) to the joint design of more medium and long-term projects.

As I said at the beginning of this article, our well-being is closely linked to the type of relationships we build, so how not to work on them, and give them the importance they deserve. It is true that our relationships are complicated by the fact of trying to fit two pieces of a puzzle that come with different forms created by the previous life, family models ... but it is also true that the handling of daily conflicts or the fact not handling them ends up being a much greater risk factor for the breakdown or discomfort in the relationship.

How many times have we ruined a pleasant moment or day by expressing ourselves from criticism, contempt, or taking a defensive attitude? How many times have we regretted not having communicated with our partner, having faced a problem, or expressed our needs?

The main problem with handling conflicts in this way is not only the amount of negative affect that we express but since time is limited and the day continues to have 24 hours and the week seven days, we are left with much less space to share positive affect and to enjoy the relationship.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist and Coach

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

Cuidar de Los Que Nos Cuidan

El deterioro cognitivo y otras enfermedades neurodegenerativas son cada vez más prevalentes en nuestra población actual, una población más longeva pero también con mayores niveles de estrés y desconexión del momento presente.

Cada vez más personas somos conscientes de estas problemáticas pero hoy vamos a hablar de otro colectivo, un colectivo a veces silencioso (o silenciado), un colectivo que disfruta, pero también sufre y que es tan demandado como necesario.

Hablamos del rol del cuidador o cuidadora, esa persona que acompaña en el día a día a quien sufre alguna dificultad como el Alzheimer y en la que diferentes estudios han mostrado la alta frecuencia con que padecen “burn-out”, es decir, el síndrome de agotamiento y estrés laboral, problemas de ansiedad y de estado de ánimo o depresión.

Obviamente el bienestar psicológico de esta profesión está altamente relacionado con otras personas: a la que cuida, la familia de esta y su familia o relaciones personales fuera del trabajo.

Desde Sinews queremos prestar especial atención a esta dinámica interpersonal ya que será una profesión cada vez más necesaria, importante y probablemente a la que muchos o nos dedicaremos de una u otra manera o de la que seremos clientes en un futuro. Vamos a ello, por tanto.

Como si de una pieza de piano se tratase, para que la melodía de la relación entre cuidador/a y cuidado/a suene tranquila, agradable y llena de bienestar hay al menos tres acordes que debemos de tocar:

1. El vínculo personal

Cuando trabajamos con personas debemos priorizar la importancia del vínculo terapéutico, por ello es importante que más allá de las labores diarias como cuidador/a se reserve un tiempo para conocerse, tanto con el resto de la familia como con la persona a la que se acompaña.

Conocer la historia de vida, los intereses personales, gustos y también las dificultades por las que pasamos nos ayuda a ser más empáticos, a entender mejor los comportamientos inesperados y las emociones.

Además poder compartir actividades e historias es una de las mejores formas de trabajar la estimulación cognitiva.

Conseguimos un 2×1 en este caso, reforzar el triángulo familia-persona acompañada-cuidador/a mejorando el bienestar y la comprensión en esta relación interpersonal y por otro lado se podrán estar trabajando áreas como la estimulación verbal, procedimental y de la memoria.

¿Cómo hacerlo?

Estableciendo un tiempo tanto al comienzo de la relación para conocerse como durante la misma, pequeños encuentros semanales dentro de la rutina o pequeñas actividades diarias en las que se comparta conversación o actividades placenteras para ambas partes.

2. La desconexión y el descanso

Precisamente por la alta carga física y emocional de esta profesión es necesario respetar los horarios de descanso del profesional, asegurando dos tipos de tiempos, uno para el descanso y la recuperación y otro para que ya recuperados puedan disfrutar de su vida personal, familia y otras actividades placenteras y significativas para ellos.

Aunque esto parezca obvio debido a la actividad frenética del día a día y a las facilidades que nos proveen las herramientas de comunicación instantánea no es siempre tan sencillo de llevar a la práctica.

La desconexión (lo cual implica como decíamos tanto descanso como tiempo para disfrutar de la vida personal) es una de las variables que más peso tienen en la satisfacción laboral y especialmente por el trabajo que realiza el cuidador/a debemos de prestarle especial atención.

¿Cómo hacerlo?

Durante el año laboral: Acordar entre las partes periodos de vacaciones.

Durante la semana: Contar al menos con dos días consecutivos de descanso y desconexión de las tareas de cuidador/a.

En el día a día: Respetar los horarios de finalización de tareas asegurando unas horas de desconexión laboral.

Pero ¡OJO! no olvidemos en qué consiste respetar esta desconexión:

- En caso de que la persona que cuida sea un miembro de la familia, el resto de ella deberá organizarse para asegurar los puntos anteriores, en caso de ser una persona contratada se deberá asegurar una sustitución.

- Cuidar no es solo la tarea en sí sino también la logística, por tanto esto debe quedar realizado dentro de las horas de cuidado, evitando así enviar mensajes o llamadas habituales para sobre citas, procedimientos, qué hacer…Evitemos por tanto la comunicación fuera de las horas de cuidado y respetemos el tiempo de desconexión y descanso.

- En cuanto a la persona que cuida, te animamos a que te concedas esa desconexión y que compartas con tu familia o círculo social lo importante que es ese tiempo para ti, tanto para descansar como para disfrutar de tu vida personal y otras actividades placenteras o de ocio.

3. El propósito de la tarea

Otra de las variables que han mostrado mayor peso en la satisfacción tanto laboral como en la satisfacción con vida en números estudios es el sentido por el que hacemos las cosas, es decir el propósito de nuestro día a día y de nuestras tareas.

El rol de cuidador/a puede llegar a ser muy rutinario pero podemos tratar de establecer objetivos como la estimulación física y cognitiva y el bienestar general de la persona cuidada. Para ello será especialmente relevante el punto uno, conocer con qué disfruta o disfrutaba esa persona antes de la aparición del Alzheimer. Las capacidades que se conservan durante más tiempo a pesar de la enfermedad neurodegenerativa son las procedimentales (como la cocina, tocar un instrumento, dibujar, la artesanía…).

¿Cómo hacerlo?

Podemos por tanto establecer actividades diarias enfocadas en ese bienestar emocional y estimulación cognitiva, con el objetivo de reforzar ciertas capacidades, como decíamos anteriormente esto además mejorará el vínculo interpersonal.

Estos momentos diarios o semanales en los que se comparte un café o comida y se intercambian historias de vida o que se realiza algo placentero y procedimental marcarán la diferencia en cuanto al propósito del trabajo y permitirán un tiempo más creativo y emocional dentro de la jornada de cuidado.

No nos olvidemos tampoco del papel de la GRATITUD al respecto, como bien sabemos toda conducta reforzada tiende a consolidarse. Reconocer el trabajo y los objetivos del cuidador/a no solo de manera económica sino con tiempo de descanso o simplemente a nivel verbal mejorará la relación y por tanto el bienestar de todas las partes.

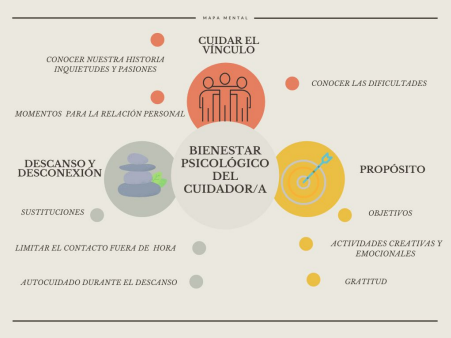

Un breve resumen gráfico para recordar esto y que nos ayudará a ponerlo en práctica

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist and Coach

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

Diary of a Global Therapist Part 4

It has been three months since the last post in which I shared my experiences working with expats from different parts of the world.

Three months of uncertainty, of continuing to hear very different stories, and of working hand in hand in managing difficulties.

They have also been three months marked by many changes, some due to the COVID-19 pandemic and others to social movements. But of course, a time in which we have not stopped working and learning.

From Sinews (and I imagine that from anywhere) we have been aware of two important and relevant changes in the day-to-day life of international companies and institutions, on the one hand teleworking and on the other the importance of respecting and empowering diversity.

Teleworking seems to have come to stay and that as a country we are approaching the European percentage of working hours from home. Although we are beginning to envision a new law to regulate it, there is much work to be done to get the most out of this new alternative.

A few weeks ago I was talking with an employee of a multinational in one of our follow-up and emotional support sessions about this new situation and it seemed very representative of what many of us live today, perhaps even because I felt deeply identified.

The employee we will call Mrs. P is working outside her home country. In her case, she has the company of her partner and children, which on the one hand appreciates and enjoys the time she can spend with them thanks to saving it on work-home transfers, but on the other hand, it has made her face difficulties, such and as she verbalized “We have been used to having a routine for so many years in which I travel, work and he takes care of the paperwork, the house, the transfers, that this situation has been almost like starting to know other parts of our relationship ”.

Mrs. P has not faced major problems with her partner, but she has experienced situations in which she has had to manage both her time and stress levels. As we mentioned in our session, despite the benefits of working from home, there are weeks in which “a waterfall of difficulties” arise in different areas.

This is how we address the importance of maintaining routines and setting limits to work. I think we have all heard a lot about this topic and about the difficulty of disconnecting when we work from home, but if we want to tackle it we should go further: what is it that makes me not disconnect, not respecting certain limits that I create myself?

For some people it may be the uncertainty and fear of the future job, for others, they need for recognition, certain personal beliefs, judgments ... or as in the case of Mrs. P the need to have everything under control, to "micro-evaluate" every detail, every possible little achievement or failure.

In our biweekly session, we talked about it and how to handle it, as well as about trying to train a kinder and more assertive communication with your family when time is required "as if by being at home you are not working" in her own words.

The session is interesting because of how representative it is of what many of us feel while teleworking, but also because it can normalize these difficulties and emotions.

I decided to write this post because the same day that I had the session with Mrs. P, in the afternoon I connected again to our online platform for the first interview with another employee of a multinational, whom we will call Mr. Q and after the two sessions I thought how much our current work and social panorama showed.

With Mr. Q I had the opportunity to address the discomfort and difficulties that he anticipated in his next project due to working with a very diverse team.

It seemed extremely sincere to me, we all know the virtues of diversity, as the famous Italian phrase "Il mondo è bello perchè è vario" quotes (the world is beautiful thanks to its variety), but this diversity is not free from difficulties and bad times.

If we want to enjoy and respect these differences, the first thing we must do is be aware of the biases we have, such as familiarity, we all tend to better evaluate what is known to us, or self-serving or group biases. , for which we will always make judgments that benefit our group and our own identity.

There begins the true work of respect and appreciation, acknowledging our evaluations, prejudices, and behaviors.

Mr. Q had a bad experience in the past with a language-related issue and acknowledges that it affects him emotionally. On the one hand, it makes him angry at the fact that he is judged for "a simple set quote" and on the other hand, it makes him feel tense in case this happens again.

During our session, we work on that discomfort and how to regulate it.

It is normal that we feel angry or in need of reaffirming our position since as Mr. Q says “I feel judged and I have to defend myself”, but I can differentiate between reacting or responding.

That is, before letting my anger and defensiveness grow I can try to give myself some extra time and to turn down the volume of my emotion in order to respond in a more rational way. Emotional regulation exercises through psycho-education, Mindfulness, and relaxation are very useful for professionals and people who work in diverse environments.

We also work not only on how to reduce discomfort and manage those difficult emotions but also on learning from the positive, that is, from the amplification of our personal strengths. Mr. Q considers himself an empathic person, in fact, he assures that his friends and family would describe him as someone who "knows how to listen".

So why not take advantage of that strength you already have? When the idea of another person or their position collides with ours and makes us feel uncomfortable, we can always turn our attention to curiosity and empathy. This is one of the practical exercises that I propose to Mr. Q:

-

Identify the discomfort, accept it and try to "turn down its volume"

-

Putting ourselves in the shoes of a researcher, asking the other person, gathering information, and finally trying to understand why they feel this way.

As we discussed in our session, these exercises help us not only to improve our emotional regulation in interpersonal situations but also to cultivate an open and empathetic mind.

We conclude the interview with a series of practical guidelines for the real management of diversity and with the possibility of having another session if necessary.

As I said at the beginning of this post, these two sessions are very representative of the problems that we currently encounter and of which we are increasingly aware of our services to international companies, educational institutions, and individuals.

For this reason, at Sinews we work to develop programs aimed at continuing to grow in this digital and inclusive “new normality”.

I finished that working day, before going on a well-deserved vacation that would last three weeks, writing the report for Mr. Q, in which in addition to detailing some practical recommendations, I recommended the wonderful book "Talking to Strangers" by Malcolm Gladwell.

Back at work and remembering those two sessions I realize that this September is different but also a new beginning in terms of opportunities and challenges in the area of mental and organizational health.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist and Coach

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

Winter Blues

Winter blues is not a diagnosis but a general term and it means feeling sad and down, melancholic and unhappy and it´s related to the shortening of daylight hours and Autumn or Winter approaching. They are often linked to something specific, such as stressful holidays or reminders of absent loved ones.

On the other hand, Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a type of affective disorder related to changes in seasons. The symptoms usually start in Autumn and continue into the winter months, and go away during the sunnier days of spring and summer. The symptoms may include:

- Feeling depressed

- Losing interest in activities you once enjoyed

- Low energy

- Problems with sleeping

- Changes in your appetite

- Difficulty concentrating

- Feeling hopeless, worthless or guilty

- Having thoughts of death

Winter blues are usually temporary and the symptoms disappear, while Seasonal Affective Disorder can last for several months.

Causes

The specific causes remain unknown, but some factors that may come into play include the changes in the circadian rhythm (your body´s internal clock), and a drop in the serotonin and melatonin levels.

Usually the happiest days are those in which we make plans; weekends.

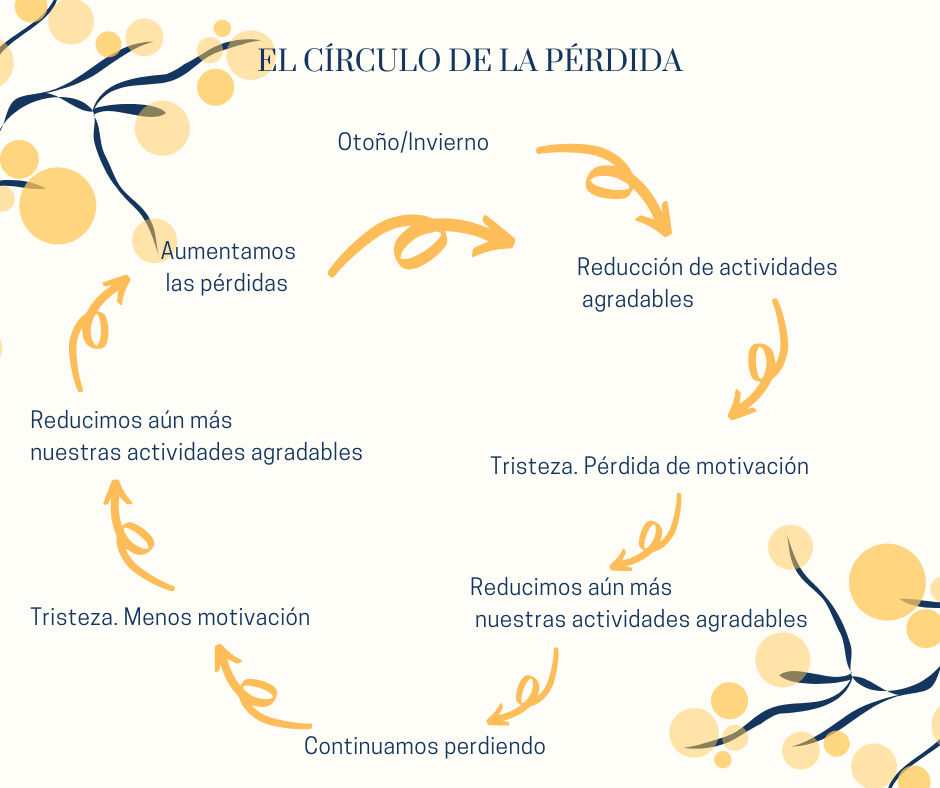

Some people also change their activity when Autumn starts. Since it´s colder and darker outside, they find it more difficult to keep up with the activities they used to do and enjoy during Spring and Summer and so when they stop or reduce these activities, there is a drop in the dopamine levels too.

There is a direct link between the number of pleasurable activities that we do and the quality of our mood. Usually the happiest days of the week are the days where people do more pleasurable activities: the weekends. In the weekends we usually spend more time with friends, we read our favourite book, play sports, and do other activities that boost our mood. This also happens when we are on holidays. When we do pleasurable activities, we increase our dopamine levels.

Strategies to deal with the symptoms

Our mood is a result of imaginary scales, where we weigh the quantity and quality of negative and positive events. The days getting shorter, the reduction of sunlight hours and the worsening of the weather conditions may lead to the reduction of outdoor activities and therefore, the reduction of positive events. If we want to improve our mood, we will then need to increase the positive events and activities and reduce the negative events when possible.

The first step would then be to increase the number of activities that we used to do and go back to the activities that we stopped doing before we started to feel low. We may use our memories and our reason and leave our actual mood aside in order to complete the following table:

| Difficulty | Level of Satisfaction | |

| Past Pleasurable Activities (Activities that we used to do but stopped doing) | ||

| Present Pleasurable Activities (Activities that we still do) | ||

| Future Pleasurable Activities (Activities that we never tried before but that we think we would enjoy) |

The first step will be for us to choose the present and past activities, and the activities that we know will take a very low effort but will provide a high level of satisfaction. For example, we cannot start by going to the gym three times a week when we have never been to the gym before. It would be easier to play guitar first if we used to play guitar in the past (low effort, high satisfaction).

Second, we will need to focus on completing the time we set for the specific activity: E.g. Playing guitar for ten minutes, instead of focusing on the results (playing a full song perfectly).

The goal is overcoming the inertia, not to obtain outstanding results in our chosen activity. So even when we don’t achieve a perfect performance, we have met our goal (to stop the circle of loss).

Here are some other tips for you to beat the Winter Blues:

- Waking up an hour early to benefit from the sunlight (So we increase our melatonin levels)

- Our brain is usually very grateful when stimulated. As winter approaches, everything gets darker and colourless. Seeking a colourful life and exposing ourselves to those colours can stimulate our brains. For example, you can go outside to a place where there is grass and colourful buildings; you can watch videos full of colour.

- Doing exercise: it is proven that exercise can increase our energy levels and reactivate our mind and body (we may need to start with low effort and high pleasurable activities and set very small goals to ourselves at first).

- Trying not to anticipate the darkness. Being conscious of the present moment and enjoying the daylight hours as much as we can.

- Being creative: Using these months to work on a goal that we set to ourselves can be a great motivation. It is important to start by taking very small steps towards that goal.

- Another suggestion is to purchase SAD lights. They do not “cure” Winter Blues but have proven to improve our Melatonin and Vitamin D levels and therefore ease the symptoms.

- Improving our diet. There are some foods that make us feel better. Eating foods with high amounts of tryptophan will naturally increase melatonin production. Tryptophan is an amino acid that our body does not produce naturally, but it is needed in the production of melatonin. Tryptophan can be found in most foods that contain protein, including almonds, oats, turkey, chicken, and cottage cheese. Also having a balanced diet and drinking lots of water can make us feel more energetic.

- Last but not least, it is very important not to be hard on ourselves. There is an explanation for our symptoms, and putting lots of pressure or judging ourselves is not going to make the symptoms better. Positive reinforcement (giving ourselves nice treats) has been proven to be more effective than punishment (self-criticism).

Remember: The more we do, the better or symptoms get, the more activities we include in our routines, the more dopamine we obtain, so the more activities we do, the less and less difficult gets to get going.

If after following these tips you still feel low and moody, CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) has been proven to be the most effective treatment for these symptoms. A qualified therapist can guide us to get through the Winter Blues symptoms.

Sinews MTI

Psychology, Psychiatry and Speech Therapy

On Children and Gratitude

How many of us can think back to our childhood days and remember our parents, grandparents and even early-years teachers urging us to say thank you when we were presented with a gift, a nice gesture or a helping hand?

I certainly remember that showing appreciation and being thankful was tremendously important for the grown-ups around me. With time, I understood that people felt good when I said thank you to them, but before empathy entered the picture, thankfulness felt like one of those things I had to do, one more rule to go by: Saying thank you was equivalent to being polite.

Politeness was and continues to be a highly valued quality among humans. One to make sure our children possess and carry with them. After all, if we stop to really be honest for a moment, we can agree that politeness speaks well of the child that practices it, while also singing hidden praises to the caregivers responsible for that child. We could agree that it is a social skill that opens doors. A win-win all around. But in this case, politesse is merely one small part of a much bigger stance: Gratitude.

And if we were conscious about the psychological weight of gratitude as general value, we would be less concerned with mere politeness. Harvesting gratitude would then become a must (something just as important as promoting mathematical dexterity, if not more).

In general terms, gratitude is associated with the capability of being thankful, but because gratitude has been the subject of psychological interest for many years, we now know that it is a little bit more complex than that.

Robert Emmons, a Professor of Psychology at the University of California, considered one of the leading scientific experts on gratitude, approaches it as a two-stage process:

According to Emmons, the first stage consists of the “acknowledgment of goodness in one's life”.

Gratefulness -therefore- begins, when someone stops to be aware of the fact that they have received something (whether it be recently or long ago).

The Second part of the process consists of the recognition that the “source (s) of this goodness lie, at least partially, outside the self”. It is then safe to say that Gratitude is directly related to humility: We are conscious of the fact that something or someone, provided us with something and that something contributed to our well-being.

To me, it all sounds like a big gift. A magical process in which we can appreciate goodness in our own existence and contact with positive emotions along the way. But that isn´t all there is to it. Experiments in the gratitude realm have directly linked it to a more optimistic look on life, increased sense of connectedness to others, longer and better quality of sleep time and fewer reported physical symptoms such as pain. (From an interview to Mr. Robert Emmons published in the SharpBrains blog on 2007).

So how can we teach our children the attitude of gratitude, which holds and includes politeness but transcends it?

- Model it. Behavioralist psychologist understood -throughout their investigations many years ago- that visually demonstrating a behavior so that it could be reproduced by the observer, was a key part of the learning experience. Is therefore safe to conclude that If you wish to cultivate gratefulness, you need to show a child what being grateful looks like. Imagine for example that you go for a walk at a park or in the woods, in the middle of autumn: It is a great opportunity to practice being grateful. You can model excitement about the fact that you get to see all the different shades of yellow, orange and red. You can open your eyes wide, and using an excited tone of voice go into the details of what you can see and are “amazed by”, ending it with a “it´s so cool or its so nice that we get to see this and be here together”.

- Create a family gratitude ritual. Depending on how the family schedule runs, you can take a moment daily to say what each family member is thankful for (at the dinner table or perhaps after reading the bedtime story…) Depending on the child’s age you will need to use simpler words such as : “I’m happy that today…x”, for example. If schedules are complex and mom can be present at bedtime, for example, but dad can´t, creating a gratitude jar is an option. Assign each family member a color of paper. Throughout the week, when someone is grateful or happy about something, they can write it down and place their piece of paper inside the jar. During the weekend, the family can make it a habit to sit down with some refreshments and read the content of the jar.

- Promote the overt expression of gratitude using thank you notes/post cards or letters. If you take into considerations Robert Emmons definition of gratitude, you will comprehend that gratitude is active and that it requires thought and intention. By encouraging our children to write thank you notes, we will be helping them to stop and think of the actions and/or gestures that someone directed at them and that were therefore, helpful, allowing them to experience positive emotions. They will also get a chance to see in return, how their words contribute to someone else’s´ emotions and day.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist

Children, adolescents and adults

Languages: English and Spanish