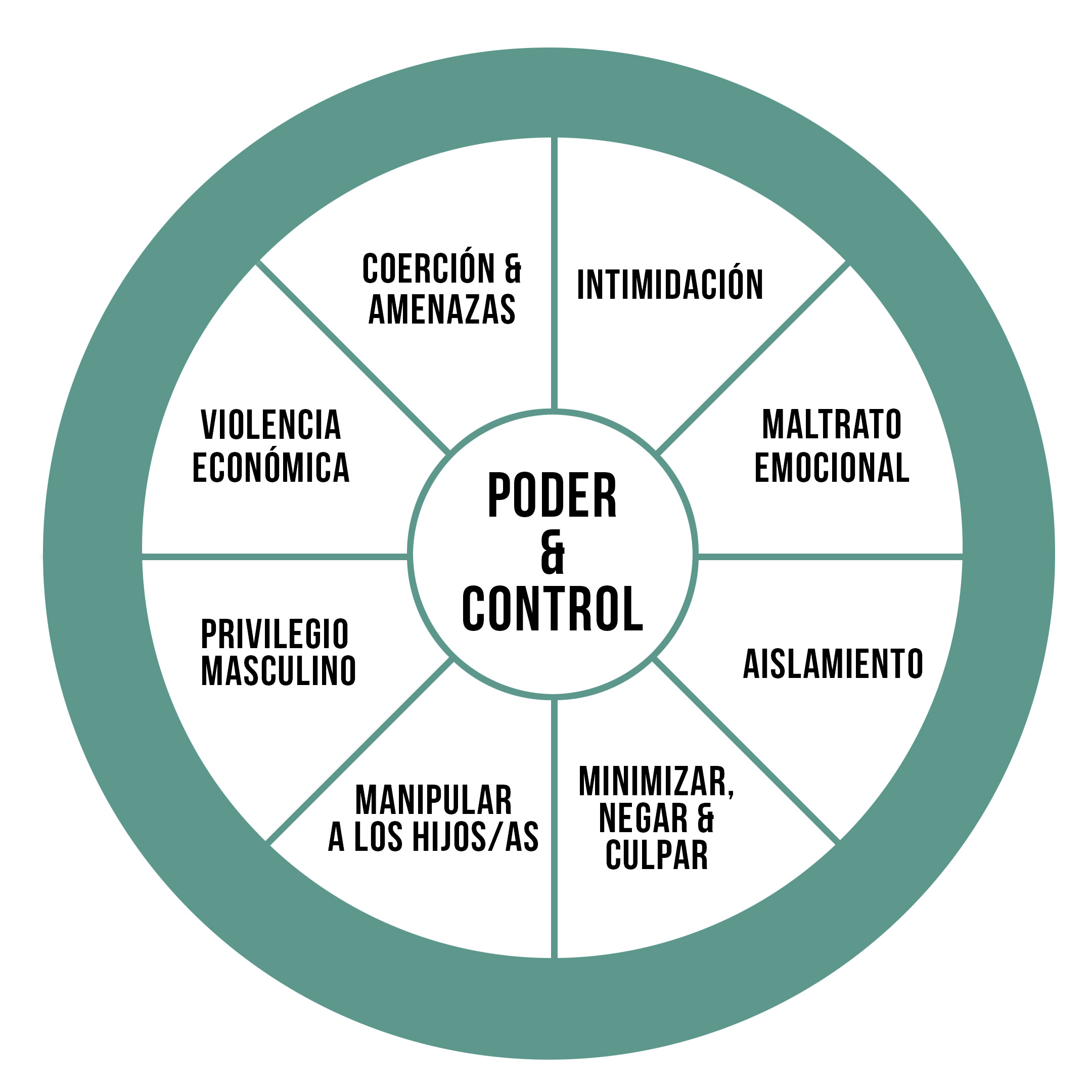

Violence against women: the power and control wheel

(The new National Agreement pact recognizes economic violence as a form of intimate partner violence)

(After several months of working together, all the political parties except right-wing Vox have agreed on a report, witnessed by our newspaper, with more than 400 points and an increase of 500 million of euros yearly in the budget, which can still be changed and will have to be voted twice to be definitive.)

The proposal mentioned in the news article, which has not yet been translated into legal changes but hopefully will be, serves to highlight that violence against women takes multiple forms. It is not just about physical assaults or murders; it is much broader and often suffered in silence or even justified.

Psychologists and psychiatrists hold a privileged position when it comes to raising awareness among victims (or rather, survivors) and perhaps preventing future violence. We have an ethical obligation to make these issues known to society as a whole, with the goal of preventing violence against women in all its forms.

Thus, these lines serve to introduce the so-called or «Power and Control Wheel» or «Wheel of Abuse,» which clearly illustrates the types of violence and their manifestations.

The Wheel

Adapted from: https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/PowerandControl.pdf

This wheel was created by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1984 to help describe violence to victims, perpetrators, judicial professionals, and society at large. The project gathered the terrifying stories of the women they assisted and documented the many ways in which men exercised violence. At the center of the wheel is power and control, the spokes represent the different behaviors that reinforce this power, and violence—whether physical or sexual—forms the rim of the wheel, as it shapes and holds everything else together.

Below are examples—by no means exhaustive—of all these behaviors, with the aim of making them easier to recognize, name, and combat, both in ourselves and in those we know, and ultimately to consign these sexist behaviors to the sewers of History.

Intimidation

To intimidate, according to the RAE dictionary, means «to cause or instill fear, to inhibit,» and this is precisely the abuser’s goal.

«Whenever I said something he didn’t like, he would look at me in a certain way, and I already knew what was coming next.»

Intimidation is achieved through looks and gestures (a technique well-exploited by actors), actions, breaking objects—especially those belonging to the woman—mistreating pets, or displaying weapons (firearms or knives, depending on the country).

The goal, of course, is for the victim to live in a constant state of fear, paralyzing her and preventing her from rebelling—just as all the world’s dictators know so well.

Emotional abuse

«He humiliated me in front of his friends, calling me useless, saying I couldn’t do anything right. Then he twisted it around, making me feel it was my fault—that I had provoked him by dropping a glass or some other trivial thing. Or he simply denied ever having insulted me.»

Emotional abuse takes many forms, some of them quite insidious or seemingly harmless:

«It’s true, though—you always drop things.»

«You have all these degrees, but you don’t know how to run a household.»

These remarks gradually sink into the victim, making her believe them and doubt herself, as seen in the well-known «gaslighting» phenomenon (which, let’s remember, originates from a 1944 film—though millennials may believe they discovered it, there is hardly anything new under the sun when it comes to intimate partner’s violence).

Isolation

«Little by little, he pulled me away from my family, saying they didn’t truly love me, that he was all the family I needed.» «If I worked late, I had to video call him to prove I was really at work.» «He forced me to give him my Instagram and TikTok passwords, meticulously reviewing everything I posted, checking who liked my posts, and blocking anyone he didn’t approve of.»

The abuser controls the woman’s actions, her social interactions—both in real life and online—where she goes, even what she reads. He may even restrict her movements outside the home and justify his actions with jealousy: «You know how I am, why do you insist on wanting to go out with other people?».

Minimizing, denying and blaming

«He told me that wasn’t abuse, that he was just being honest when he humiliated and insulted me because I was useless.» «‘You’re just asking for it’ was his favorite phrase.»

The abuser repeatedly denies the abuse or downplays it: «What are you complaining about? It was just a little slap, nothing serious.» He shifts the blame onto the victim, portraying himself (and often extending this to «real men» in general) as a helpless bag of hormones who reacts instinctively to so-called provocations, with no ability to reflect.

Sadly, these justifications are widespread in society, sometimes wrapped in paternalistic rhetoric: «It’s for her own good, poor thing.» This exposes the deeply ingrained view of women as weak, fundamentally different from men, and in need of protection—even against their own will.

Using children

From the almost comical portrayals in sitcoms—»Tell your mother to pass me the salt»—to the most extreme cases of vicarious violence, where children are murdered to inflict eternal pain on the mother, it is clear that abusers know how to strike where it hurts most. They manipulate the mother’s guilt, threaten to «take the children away,» use visitation rights as an opportunity to harass her, and manipulate them—actions that have even been legitimized by certain psychiatric sectors (such as the now-discredited Parental Alienation Syndrome).

Male privilege

«In his free time, he writes articles that get paid, so it’s only natural that I have to handle all the housework when I get home from work.» «He said I was his wife, and to him, that meant his maid.» The man defines and enforces rigid, unchanging gender roles, acting as the lord of the castle, imposing his own rules. And if this seems outdated, as these chilling examples from traditional proverbs show: «Women should be seen and not heard.» «Keep your woman barefoot and pregnant.», let’s think on the rise of the tradwife movement and the resurgence of outdated debates on household chores, childcare, and career choices.

Economic Abuse

The news article that introduced this text highlights one of the most common forms of violence against women: financial abuse. This takes various forms, such as giving her a monthly allowance (like a child’s pocket money), keeping her in the dark about family finances, preventing access to accounts, forcing her to ask for money, prohibiting her from working, even taking out loans in her name, leaving her in debt even after divorce.

It is also striking how the abusers forget who the alimony money is for, withholding payments as leverage to exert control.

Coercion and threats

«He told me if I wore that skirt to class again, he’d take it away.» «Yesterday, I got a WhatsApp from him—if I leave him, he’ll kill himself. How can I do that?» «If you don’t drop the charges, I’ll kill your dog.»

Threats of harm, abandonment, murder, involving social services, forcing her to commit crimes—anything goes for the abuser, including suicide threats to induce guilt.

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS, Madrid, with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Foto de Darina Belonogova: https://www.pexels.com/es-es/foto/persona-mujer-cama-sentado-7208920/

Foto de Liza Summer: https://www.pexels.com/es-es/foto/mujer-en-camisa-de-manga-larga-beige-6383201/

The Universe of Anxiolytics: Which One Might Help Me Best?

– I’ve been diagnosed with anxiety. Which is the best anxiolytic?

+ Let’s take it easy and start from the beginning.

– And what is the beginning?

+ Well, even from the Bible, the beginning is always the word: «anxiolytic» literally means something that calms anxiety. However, nowadays, we use many different medications from various pharmacological groups.

– Are there that many?

+ Yes, quite a few. Antidepressants like sertraline or escitalopram; antipsychotics, such as olanzapine or quetiapine; antihistamines (hydroxyzine); antiepileptics (pregabalin, gabapentin); beta-blockers (propranolol); and finally, what most people understand by anxiolytics without any qualifier, though they are also known as hypnotic-sedatives, are benzodiazepines (alprazolam, lorazepam, diazepam). For historical interest, although they are no longer used for anxiety but are still beloved by the media, let me mention the barbiturates.

– Wow, that’s a lot of names. You doctors must be something special to be able to remember all these terms.

+ And pronounce them without biting our tongues, yes 😉

– Could you explain to me how medications are named, since we’re on the topic of words?

+ Very briefly. When a drug is in the development phase, and it’s not yet known whether it will be useful or not, it’s given a “code name,” consisting of letters and numbers, such as UK-92,480. Once its efficacy is confirmed, it receives a name related to its chemical structure and the family it belongs to (let’s imagine lormetazepam): this name is the “generic” or “international nonproprietary name,” by which it will be known worldwide, with slight variations depending on the language. Finally, when the company markets it, it assigns a brand name made up by the marketing department or based on some of its characteristics (e.g., Atarax – hydroxyzine – an antihistamine with anxiolytic properties, from the Greek ataraxia, meaning imperturbability, serenity). I should also point out that the brand names I’ll be using here are for educational purposes only and do not reflect any commercial interest (I have no ties to the pharmaceutical industry).

– I understand now. Back to my initial question, out of all those options, which is the best for anxiety?

+ That will depend on many factors.

– Such as…

+ The first and probably most important is the type of clinical presentation. I’d also like to remind you that psychotherapy is the most appropriate treatment for mild anxiety disorders and should be combined with pharmacological treatment for moderate cases.

– So, not everyone with anxiety should take medication, right?

+ Exactly. You might not even need to do anything at all—remember that anxiety is an innate emotion (we are born with it) and can even be adaptive. For instance, normal anxiety the first day at a new job pushes us to do better. However, when it’s so exaggerated that it paralyzes us or has very negative consequences on life, leading to unnecessary suffering, it obviously needs to be treated.

– So, which is the best medication? Antidepressants, despite their name?

+ Probably yes. Nowadays, most anxiety disorders are treated with antidepressants. Regarding specific diagnoses, panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia), social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, the most common ones, have antidepressants as their first line of treatment.

– Without being depressed at all? Isn’t it that most cases involve a mix of anxiety and depression?

+ There’s some truth to that. But even in pure anxiety, without any depressive component, antidepressants are the first-line treatment.

– Do all antidepressants work?

+ Almost all of them. The most notable exception is bupropion, which is not effective. The most commonly used nowadays are the well-known SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), and among these, current guidelines recommend sertraline as the first option. Other widely used ones include escitalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine.

– So, I just take a pill, and my anxiety will go away forever?

+ Well, magic belongs to others, unfortunately. Antidepressants work differently: you need to take the treatment every day, and gradually, the anxiety will decrease. Also, it’s not uncommon for it to get worse at the beginning.

– How gradually? How long does it take for the antidepressant to work?

+ Here, I’m afraid, you need to be a “patient” patient. In all cases, we’re talking about weeks to achieve full remission, and although there is considerable interindividual variability, a minimum of about 2 weeks is required to see effects.

– But if I’m feeling really bad, how do I survive that time until the antidepressant kicks in?

+ That’s where the other groups I mentioned come into play. Let’s start with the main one, benzodiazepines—benzos for short. They are pure anxiolytics (meaning they are not antidepressants), but they also have other actions, the most well-known being that they are good muscle relaxants, hypnotics (sleep-inducing, making you sleep), and even antiepileptics. They take effect immediately, last for hours, and then are eliminated, but…

– If they’re so good, that “but” must be the size of a mammoth.

+ BUT, as I said, they make you sleepy (which is bad if we intend to take them during the day and lead a normal life), slow you down, decrease reflexes and balance, impair memory while under their effects, are lethal in overdose, have potential for abuse and addiction, and can be diverted for illicit purposes as well.

– So they’re terrible! How can they be among the best-selling medications?

+ Because they’re truly effective for their intended purpose, which is to eliminate anxiety, and when used properly, they are extremely useful. The most well-known include bromazepam (the famous Lexatin, as in the popular expression “Lexatin omelette”), lorazepam (Orfidal), and alprazolam (one of the strongest benzodiazepines, with a brand name in Spain that alludes to its action, Trankimazin -it’s known as Xanax in US, nice name anyway).

– How should they be taken?

+ Exactly as prescribed by the doctor… to avoid the risks we mentioned earlier. With this medication, it’s especially important to follow the prescribed regimen and inform your healthcare provider if you deviate from it. In panic disorder, for example, benzodiazepines are often used initially along with the antidepressant to cover the time it takes for the latter to start working, and then they are tapered off within weeks.

– What happens when they are prescribed “SOS”?

+ It’s also called “as needed,” “rescue,” “PRN” or “if necessary.” It’s a very useful way to take benzodiazepines. It means they are not scheduled, not taken daily or anything close to that, but only when the person feels they can’t control the anxiety or are in the middle of a crisis. Often, just carrying around the pill is enough to provide reassurance and avoid taking it, almost like a talisman. To draw an analogy, it’s similar to having paracetamol at home. Not every time we have a headache do we take it; we know that sometimes just sleeping or doing something entertaining will make it go away, but if we need it, it’s there, and that’s enough.

– Which one is the best then?

+ There isn’t really a best or worst. They differ in terms of the speed of action, strength (the amount needed to exert its effect), duration of effect, probability of “rebound” anxiety, metabolism… depending on what you’re looking for, you’ll choose the appropriate compound.

– And the other types of drugs you mentioned?

+ Some antihistamines (first generation, which cross into the brain) produce a non-specific “sedation” and a sense of calm: the most commonly used is hydroxyzine. Certain antipsychotics (mainly olanzapine and quetiapine) are also used for their sedative effects, as well as antiepileptics called gabapentinoids, pregabalin, and gabapentin, which share with benzodiazepines their action in favor of the calming neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). All of these are certainly useful, especially when, for some reason, we want to avoid using benzodiazepines. The most common reason being the risk of addiction.

– Without having a crystal ball, how do you know if someone is going to become addicted to benzos?

+ Indeed, we can’t know for sure, but remember that the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior: someone with a history of substance use is likely to have problems. This is especially true with alcohol: the combination of alcohol and benzodiazepines is one of the most dangerous in my field.

– Are the other drugs better and safer than benzodiazepines?

+ The other drugs also have their own side effects and issues; no medication is free of them. Even water itself is dangerous in excess. But they certainly offer several advantages, especially in terms of their zero potential for addiction and misuse.

– You haven’t mentioned that other drug with the difficult name, propranolol.

+ Propranolol, and a few others in its group, the beta-blockers, are indicated for a very specific form of anxiety, “performance anxiety.” In certain circles, it’s known as the “exam pill,” and it’s also very popular among those giving a lecture or, more modernly, a presentation.

– How does it work?

+ It’s the only one of all the medications we’ve discussed that doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier, meaning it doesn’t reach the brain. Its action is to reduce all the “peripheral” anxiety symptoms, i.e., those related to the body rather than the mind: tachycardia, sweating, tremors, dry mouth… and in this way, we convince ourselves that we’re not anxious. It’s ideal for oral exams, theatre actors, and all those situations where the sedative effects of other drugs are not desirable. Obviously, antidepressants don’t sedate either, but as we said at the beginning, they’re not effective in the moment.

– We’ve really covered pharmacology. Any final message?

+ The usual: listen to your doctor and trust Sinews, we’re here to help.

– Wait, I almost forgot, what about herbal remedies? That trendy one with the difficult name?

+ Phytotherapy is probably better left for another day; it’s getting late today.

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS, Madrid, with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

How does menopause affect mental health?

«I had always slept well, only major Troubles kept me awake. And then menopause came. I never slept through the night again.» Ana, in my office.

«I hadn’t wanted to have children, but by choice. From that moment on, the freedom to choose no longer existed. I went through a grieving process for the melancholy of what can no longer be. It was tough. If you add to that the physical changes I’ve had, the hot flashes that have prevented me from doing my job normally, my life normally, anything normally, well, it was a difficult process.» Mamen Mendizábal, journalist. «Let’s talk about menopause» El País Semanal, May 5, 2024.

«I’m losing it, I cry over anything, I snap at the slightest remark, I can’t even put up with myself. No one tells you what this is like, they talk about little hot flashes and that’s it, we’re invisible.» Raquel, in my office.

Menopause is one of the most notable members of the group of things that are never said, you know, the poor relatives of the things that are always said (A. González-Cano). This lack of information and the culture of shame, along with the absence of this topic in any media, has been the dominant theme for centuries, to the point that the 500-page book! by Canadian-American gynecologist Dr. Jen Gunter «The Menopause Manifesto» (Citadel Pr, 2021) was a best-seller: it aimed to dismantle myths, put an end to instilled fears, and empower women through objective and truthful information.

In its simplest biological definition, menopause is marked by the end of menstrual periods (as an expression of ovarian insufficiency) and is a «non-diagnosis» established retrospectively after 12 months without a period. Prior to this moment, there is a variable time of menstrual irregularities, called «perimenopause,» which represent a change from the previous pattern, and the term «perimenopause» encompasses all these phenomena. Although the lack of menstruation is the most obvious manifestation of menopause, it is the ovaries (and their hormones) that are «failing»: they stop producing eggs and the hormones that mark the fertile years of a woman’s life. This lack of steroids affects multiple systems and increases the risk of diseases, related to osteoporosis, dementia, and heart disease.

It is not a disease, and yet, we talk about «symptoms» and «treatments.» The medical community oscillates between ignoring it «it’s a natural phase, just use a fan for hot flashes and that’s it» and prescribing indiscriminately: there are already voices warning of the excessive medicalization of menopause. It’s worth remembering that there are as many menopauses as there are women, and that each decision about possible treatments will have to be individualized and agreed upon.

The «symptoms» or clinical manifestations considered cardinal in menopause, based on their association with the transition and the possibility of being treated with hormones, are four: vasomotor symptoms/hot flashes, genitourinary symptoms, sleep disturbances, and mood difficulties. All of them belong directly to the field of mental health or have a considerable impact on it.

Vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes)

Experienced by up to 80% of women, they are the rule more than the exception: they appear on average 4.5 years after the last menstrual period and last a median of 7.4 years; they «tend» to disappear after a few years, but many women experience them for more than a decade. About 50% of women who have these symptoms before menopause will have them persistently 10 years or more after their last period.

They consist of a wave of heat that starts in the upper chest and face and then spreads throughout the body. Those happening at nighttime are called «night sweats» and greatly disrupt sleep. Some women suffer a few in their lifetime while others have several every hour, with a huge impact on their daily lives.

Treatment ranges from what we could call «common sense remedies» (fan, dressing in layers), to avoiding triggers (alcohol, caffeine – in some women), and also cognitive-behavioral therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, non-hormonal medications (antidepressants, clonidine, gabapentin; only paroxetine and fezolinetant are FDA-approved for this indication), and hormones in various formulations. Other approaches, such as yoga, exercise, consumption of omega-3 fatty acids, and black cohosh, have not been shown to be effective.

Genitourinary symptoms

Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and urogenital symptoms are less common than the former, but still very common, in 25-50% of women. They include dryness, chronic irritation or burning of the vagina and vulva. There may be bleeding and pain during intercourse and lack of lubrication. There is also increased frequency of urination with little output, dysuria (discomfort when urinating), urethritis, and frequent urinary tract infections.

These problems theoretically reflect the lack of hormones and the absence of exposure to estrogens of the vaginal epithelium and urinary tract. Unfortunately, and unlike vasomotor symptoms, symptoms of menopausal genitourinary syndrome do not spontaneously resolve over time. They are, however, very effectively treated with topical treatments: estrogens, moisturizers, or lubricants. Although it has become fashionable, laser treatment of the vagina does not improve these troublesome manifestations.

Sleep disturbances

If the two previous problems obviously influence mental health, this one has a significant impact: in fact, some authors believe that menopausal mental disorders are largely secondary to poor sleep, although not all (epidemiological) studies find a clear relationship between ovarian insufficiency and sleep. Women with more sleep problems are those with insomnia at a younger age, long before menopause, as anyone could venture. And let’s remember that getting older is associated with worse sleep, so it is not always easy to decide which factor is the «culprit.»

It is clear that night sweats greatly worsen sleep, causing multiple awakenings and poor-quality sleep. Furthermore, even without hot flashes, the sleep architecture in menopausal women shows more disturbances in the second half of the night, with disruption of REM sleep. It is important not to attribute to menopause all sleep problems in women of this age, and to make a diagnosis by ruling out other disorders (sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, etc.) as in other times of life.

Mood disorders

Here we enter fully, without excuses, into mental health. Mood problems have a complex relationship with menopause. Depressive symptoms are associated with nocturnal hot flashes and sleep disturbance, indicative of the close relationship between sleep and mood. Multiple well-designed studies have identified the menopausal transition as a vulnerable period for depression in middle-aged women; during this period, the likelihood of experiencing new-onset depression is 2-4 times higher. Anxiety and concomitant hot flashes predict major depression during this time.

It is clear that, although hormones (or their absence) are ultimately responsible for these problems, in cases of moderate and severe mood disorders, hormone therapy is not the first-line treatment. Otherwise, since it is often difficult to unravel the various contributing factors to mood changes (hot flashes, sleep disturbances), it is better to do a short trial with hormone treatment, if possible, rather than using multiple specific compounds for mood, sleep, and hot flashes to determine which symptoms are due to the menopausal transition and which are independent of it.

To treat or not to treat?

Let us remember the phrase from the beginning: there are as many menopauses as there are women. This means that the decision to use treatments and which ones to use will have to be individualized in each case.

Regarding mental health problems «triggered,» «caused,» or perhaps simply «associated» with menopause, a reasonable option would be to consider this as just one more of the innumerable «etiologies» or factors associated with mental disorders, that is, to treat them when possible or desirable, using strategies appropriate to the severity of the disorder, and always agreeing on the therapeutic approach with the woman. This is an exemplary field of the healing power of what we pompously call «psychoeducation»: listening attentively to what is happening and explaining it in simple terms away from scientific jargon to truly empower the woman and allow her to make her own decisions.

And I would like to end these lines with a reflection addressed to all those who are raising their voices against what they consider to be an «excessive medicalization» of menopause. With the current level of development we enjoy, this seems like a sterile debate. So many things that were considered natural a century ago, like pain, deadly infections, early mortality, have ceased to be so thanks to that alleged medicalization that is not a subject of debate. Why should menopause be any different? For the same reason that analgesia during childbirth generated so many – fortunately overcome – controversies? (Curiously, I have never heard any prominent author complain about the excessive medicalization of renal colics, also very natural for all those whose kidneys are prone to fabricating stones). Or perhaps it is because menopause has been invisible and so should remain? In the words of Dr. Gunter, «There is no greater act of feminism than talking about a menopausal body in today’s society.»

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS, Madrid with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Can I safely reduce my paroxetine dosage if I feel well and have no depressive symptoms?

Question

Hello, I have been on paroxetine for nearly 10 years. First at 30mg and more than a year ago I proposed my doctor a dosis of 20mg which he said try it and see what happens. So far nothing. I drink wine and the occasional beer with no negative effects that I know of. I’m now thinking to reduce to 10mg. This WITHOUT consulting my doctor. I do yoga meditation and on the few occasions I feel a little anxiety, breathing does wonders. So, what is your opinion. Please note I feel fine with no depressive symptoms. Thank you.

Answer:

Hello,

First, let me congratulate you for taking the initiative to taper your medication and mastering the non-pharmacological techniques of addressing anxiety! That’s the kind of “active” patient I like best. That said, when someone sitting in front of me in my office states something similar, I always make sure to asses several questions before giving a definite answer:

- What was the medication originally prescribed for? As you know, antidepressants such as paroxetine have various indications, such as depression and anxiety (social, generalized anxiety, panic disorder), the most obvious, but also posttraumatic stress disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as the so-called “off-label” use (not approved by FDA or other regulatory agencies, but widely used, such as chronic pain).

- How has the original disorder evolved? Was it completely resolved with the antidepressant? Did it ever recur? When?

- Has the patient done psychotherapy as part of the treatment? Did it help? Still useful?

- What was the rationale for the duration of the medication? What were the goals of treatment? Were they met?

- Has there been any attempt to taper the medication? When? Was it successful? Was the medication restarted again?

- Why does the patient want to decrease the dose right now? Are there any troublesome side effects that weren’t important before and have become an issue now? For example, pretty typical of paroxetine, weight gain, sexual side effects (lack of sex drive, erectile dysfunction, anorgasmia).

- Is this the right time to try? Are there any vital changes coming, such a different job/city/country, interpersonal relationships losses/gains? A sound principle is to modify one variable at a time, in order to know which one is responsible for the success/the culprit in case it goes wrong.

- Have the patient ever experimented any withdrawal symptoms? From missed doses, for instance, or on a trip when they forgot their medication. Withdrawal symptoms can get very nasty.

- What is the best approach to the tapering? Are 10 mg-decrements for paroxetine enough to avoid withdrawal symptoms? Do we need other strategies?

- Is there a “plan B” in place should the tapering fail? Patients often need reassurance, a change of approach maybe, other measures.

So, as you can see, it’s not as easy an answer as yes, go ahead! Or no, don’t try it at home! My best advice is indeed do tell your doctor, and follow their instructions, or contact another doctor if the first one is not available.

I wish you all the very best.

Abouth the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS, Madrid with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Let’s talk about grief

Grief is the response to a loss: we use this term for losses of health, work or even the country of origin when immigrating, but in this article we will reserve it for the most frequent and probably most important loss, the death of a loved one. Bereavement is then the loss itself, and grief, the response.

The Western society we live on has justly discarded the rigid impositions of mourning, all those characteristics of attire and behavior required of the bereaved, with their well-demarcated deadlines (deep mourning -dull black fabrics, ordinary or second mourning -jewelry and white trims in dresses, and half-mourning -purple, lilac and gray) according to the relationship with the deceased. But along with these now laughable demanda, feelings, tears and grief, which of course are still there when someone we love dies, have also slipped down the drain of History. Let’s talk about grief, or better yet, let the poet speak:

H. Auden, Funeral Blues (1936-38)

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling in the sky the message He is Dead,

Put crêpe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last forever, I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun.

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Thus, grief comprises thoughts, feelings, behaviors and physiological reactions; its experience is influenced by multiple and highly variable factors; we will see that the picture progresses from acute, intense and disruptive grief to the so called «integrated» or resolved grief, in which the loss is «integrated» or incorporated into the life experience leaving a bittersweet aftertaste. This progress is often erratic and can be difficult to ascertain while it is happening. The well-known stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance) do not always or necessarily occur in that order (sorry, Dr. Kübler-Ross). And of course, neither there is a fixed time to go through these phases and reach grief resolution. Let’s start at the beginning, then.

Acute grief

The hallmark of acute grief is an intense focus on thoughts and memories of the deceased, accompanied by sadness and yearning. The poet guides us to its characteristics:

- Intense feelings of yearning for the deceased person.

- Insistent thoughts and memories of the lost person that preoccupy the mind, sometimes including hallucinations.

- Frustration and sadness due to the impossibility of being back together.

- Atraction towards objects and activities associated to the deceased.

- Disrupted appetite and sleep, as well as somatic symptoms such as heart palpitations and dizziness.

- Social withdrawal and disinterest in other people and activities.

- Confusion about one’s identity and feeling lost without the deceased.

- Disbelief and difficulties in accepting the loss.

- Impaired attention, concentration or memory.

The attachment theory states that we humans are biologically motivated throughout life to form secure, close relationships with a few other people. These are the people whom we love and who reciprocate love: they provide a «safe haven» to return to in periods of a stress and a secure base from which to explore the world, learn and adventure. Our loved ones contribute to our sense of identity and belonging. Representations of attachment relationships are internalized, tend to be stable and resistant to change, and influence multiple aspects of daily functioning, both conscious and unconscious.

Then, grief disrupts the attachment: the learning period in which the internal representations of the deceased are not aligned with the reality of the loss and the disruption of plans and goals mark acute grief. As we become fully aware of the irreversibility and the consequences of the loss, the mental representation of the attachment is revised y one’s goals and plans are redefined. There is still an internal connection with the deceased, but the nature of that connection has changed.

Let’s remember that, statistically, most of us will die «of old age», and most people grieve with the support of family and friends, moving gradually over time from acute to integrated grief.

Factors influencing grief

Multiple factors are involved in the experience of grief and its expression («mourning»). What follows is an attempt to systematize the elements involved, not pretending to be exhaustive.

- Relationship with the deceased: of many deaths we say in Spanish «es ley de vida», it’s the law of life. It’s obvious that the more this law of life is fulfilled, the more likely it is that the grief will be integrated without problems. Thus, studies agree in pointing out that the most complicated griefs are those secondary to the death of a child. But we must also consider the roles a person plays: let’s imagine a conventional couple, together «forever»: the widower has also lost his cook, cleaner, housekeeper, community manager and even a stylist/personal shopper who chooses his clothes every day. The widow, for her part, will be left without a driver, plumber, electrician, handyman and tax adviser. It is not surprising that in the Netherlands, whose euthanasia law dates back to 2001, joint requests for euthanasia are on the rise.

- Type of death: sudden, violent or accidental deaths produce a relatively intense acute grief, while those secondary to long illnesses allow a progressive adaptation to the loss, the famous «anticipated grief» that saves suffering when death finally occurs. Of all the types of death, those due to suicide are the most complex.

- Cultural factors: these comprise both those factors not specific of grief (race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religious affiliation, community, conceptualization of distress, psychosocial stressors and supports, ways of coping and seeking help) and the specific ones (funerals, rituals after the death, people attending and expression of grief of mourning by community members, occasions for remembrance, specific grief practices, community beliefs).

Grief and health

The association between grief and health issues, both physical and mental, is well known. The bereaved are more likely to suffer multiple diseases, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, arthritis, cancer, diabetes and hepatic cirrhosis: the weakened immune system secondary to stress, unhealthy lifestyles (increased alcohol use, smoking, worsening nutrition), missed medical appointments, poor quality of sleep and the involuntary loss of weight that often accompany bereavement probably contribute to these results. Moreover, all-cause mortality is also increased, and this increase will possibly last years.

And as far as mental health is concerned, many of the characteristics of acute grief fall squarely into this field. With the goal of not «pathologizing» grief, it is advisable to make a «differential diagnosis» of it with major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder above all, and with prolonged grief disorder, which we’ll discuss below.

Despite the fears raised when the DSM-5 removed the bereavement exclusion (which did not allow a diagnosis of major depression to be made within 2 months of the death of a relevant person), studies have shown that physicians are able to distinguish between these conditions, and there is no undue «medicalization» of what is ultimately an inescapable part of life for most.

However, it is necessary to diagnose and treat the mental disorders associated with grief, in which grief acts as a precipitating or aggravating factor: depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, PTSD, sleep and somatoform disorders, substance abuse and the prolonged grief disorder with which we will end this writing.

Prolonged grief disorder

Historically, it has been called chronic, complex, complicated, pathological, traumatic and unresolved grief, but the term «prolonged grief» has been chosen and is included in the DSM-5-TR and the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). This is a condition differentiated from acute grief by the persistence of strong emotions and/or obsessive thoughts about the deceased associated with significant distress and/or impairment for a prolonged period of time, at least 6-12 months after the death.

Studies have found that the prominence and persistence of certain elements of grief may herald a prolonged grief disorder:

- Imagine alternative scenarios.

- Blaming oneself or others for the death.

- Judging one’s own grief.

- Catastrophic ideas about the future.

- Avoid reminders that generate intense grief, such as activities shared with the deceased.

- Excessive focus on trying to feel close to the person through sensory stimulation, such as smelling their clothing, listening to their recorded voice, or viewing photos and videos.

- Problems regulating intense emotions.

This condition is considered to have a specific psychotherapeutic treatment, reserving psychotropic medication for concomitant disorders.

And these lines will end with a couple of sentences that sum it all up: grief is the form that love takes when a loved one dies, and the adaptation to that loss is that the connection with the deceased gradually moves from preoccupying the mind to reside comfortably in the heart.

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Self-injury in adolescents: the six W’s

Self-injury has become a public health concern in adolescence and a growing phenomenon in other age groups. It is present in books, movies, and social media, to the extent that platforms like Instagram prohibit its dissemination (prohibiting what it does not exist wouldn’t make much sense). Different studies yield alarming rates, showing an exponential increase in the last 10 years.

This article aims to shed light on this behavior using the journalistic model of the 6 W’s: what, who, when, how, why, and where.

What

Self-injury, also known as self-harm, is defined as an act carried out by a person with the intention of harming themselves. It can be associated with varying degrees of suicidal intent, but this article focuses on non-suicidal self-injury, as it is considered a distinct entity from suicidal behavior. However, it’s important to note that self-injury and suicide are related, with estimates suggesting that individuals who self-injury are four times more likely to attempt suicide and 1.5 times more likely to die by suicide. This underscores the significance of the problem. For the sake of brevity, this article uses the term «self-injury» without specifying, particularly in the adolescent population due to its frequency.

Thus, by definition, the following are NOT considered self-injury:

- Acts with suicidal intent, regardless of the final outcome.

- Socially accepted practices like tattoos, piercings, or religious rituals.

- Accidental injuries.

- Indirect self-injury through behaviors such as eating disorders (anorexia and bulimia) or substance use (alcohol, tobacco, other drugs).

Who

Prevalence data from pooled community-based studies indicate that 17% of adolescents (10-17 years), 13% of young adults (18-24%), and 6% of adults (25 and older) have self-injured at some point. In clinical populations (adolescent psychiatric patients), the figures escalate to 50-75%.

- Gender (binary): There are no significant differences, although some studies show a slight female majority.

- Sexual and gender minority groups: Compared with those identified as heterosexual, the prevalence of self-injury is higher in youth who question their sexual orientation or identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Studies also indicate higher prevalence rates of self-injury in transgender adolescents.

- Race/ethnicity: No consistent differences, as self-injury occurs in individuals from all ethnic backgrounds.

- Risk factors: let me insist that risk factors are those that studies have identified as associated more frequently to the behavior, but never in 100% of the cases. In self-injury the following have been identified

-

- History of self-injury.

- Personality disorders belonging to cluster B (borderline, histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial)

- Hopelessness

- Psychopathology: depression, eating disorders, emotional problems (depressed mood, social withdrawal), behavioral issues (aggressions, criminality, substance use).

- Sleep problems, emotional dysregulation, emotional distress, impulsivity.

- History of childhood abuse.

- Stressful or negative life events, including bullying and victimization by peers.

- Exposure to self-injury by friends and peers.

- Parents with psychiatric issues.

- Family dysfunction.

- PROTECTIVE FACTORS on the other hand, have received less research attention. Possible protective factors for adolescents include self-esteem, self-compassion, positive personality traits (e.g., warmth, friendliness, carefulness and vigilance), and satisfaction with social support. For sexual minority adolescents, feeling connected to others (parents, other adults, and friends) and feeling safe in the academic environment have been identified as potential protective factors.

When

In self-injury, as is the case in almost everything, age does matter: Typically, it begins between the ages of 12 and 14, although onset before the age of 12 is possible but rare, especially in children under 7 years old. Self-injury in those under 12 is associated with more frequent acts, more self-injurious methods, and more hospital visits due to them.

Many individuals who engage in self-injury do so only once, and most who engage in this behavior during adolescence cease doing so by the end of adolescence or the beginning of adulthood. Additionally, women are more likely to continue self-injuring into adulthood compared to men.

Regarding the timing of self-injury, in the vast majority of cases, it occurs in solitude and in response to triggers discussed in the «why» section.

How

People who self-injury employ various methods, including:

- Cutting the skin with sharp objects like knives, razors, or blades, often leading to bleeding and possible linear scars. This is the most common method, chosen by an estimated 70-90% of those who self-injury.

- Carving words or symbols into the skin.

- Burns with cigarettes and other objects.

- Hitting the head or other parts of the body.

- Scratching until bleeding.

- Biting until bleeding.

- Rubbing the skin with rough surfaces.

- Interfering with wound healing (e.g., picking at scabs).

Self-injury usually occurs on the arms, hands, wrists, and thighs, although it can be anywhere on the body. Women tend to self-injury more on their arms, wrists, and thighs, avoiding the face, genitals, and breasts. In contrast, men may choose to self-injury on the chest, face, genitals, and hands. Most injuries are superficial and do not require medical treatment, though some individuals unintentionally harm themselves more severely than intended.

It’s noteworthy that individuals who self-injury often have a higher physical pain tolerance, tolerate pain better, and experience less pain intensity compared to those who do not self-injury. Many (33-50%) do not feel any pain during self-injury, while others view it as a reward or reinforcement.

Why

This is the most crucial question, with the hope that understanding the «why» will help us assist these individuals. However, it’s often challenging to explain the motivations behind one’s behaviors.

Nonetheless, numerous studies have attempted to answer this question by examining factors and events immediately before and after self-injury. An empirical model with four primary «functions» has been constructed, suggesting that self-injury is caused and maintained by one or more of the following:

- Negative intrapersonal reinforcement: Self-injury reduces (regulates) negative and aversive thoughts and emotions such as anger, sadness, and anxiety.

- Positive intrapersonal reinforcement: This behavior generates desired feelings and thoughts (e.g., feeling something "even if it's pain" or satisfaction from self-inflicted punishment).

- Negative social reinforcement: Self-injury facilitates escape from unwanted social demands and unbearable social situations (e.g., allowing a student to stay home from school).

- Positive social reinforcement: It elicits a positive response from others, such as attention or support from family and friends.

Most individuals report self-injuring as a means of emotional regulation, to manage negative emotions, with the inherent risk of developing addictive tendencies and substituting more adaptive coping strategies. Additionally, the following factors contribute to self-injury:

- Attributional style and hopelessness: Individuals most vulnerable to self-injury are those who attribute negative life events primarily to internal (rather than external), stable (non-transient), and global (non-specific) causes. For example, after a breakup, they may attribute it solely to their own perceived flaws, which they see as stable and preventing them from ever having a successful relationship (global).

- Self-criticism: Multiple studies link self-criticism to self-injury, using terms like negative self-image or self-evaluation, self-disgust, and self-hatred.

- Implicit identification: Over time, individuals develop a strong association with self-injury, choosing this behavior in times of distress instead of more adaptive coping strategies.

- Social factors: Self-injury has been linked to childhood abuse and various influences from the peer group, including bullying, loneliness, social isolation, loss of significant individuals, victimization by peers (including cyberbullying), and social contagion (beware of fads!).

- Biological factors: Some studies suggest genetic influences, alterations in the opioid system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and certain brain areas.

Where

Allow me to make a slight shift from the «where» of self-injury to the «where to treat it,» in other words, its treatment, if deemed necessary (remember that a significant portion of self-injury occurs only once). An essential aspect is the attitude of friends, family, other adults, and professionals toward self-injury: here, too, finding a balanced approach is key. Self-injury should not be trivialized because it is undoubtedly significant, but it should not be treated with the same urgency as crimes or suicide attempts.

The most reasonable approach is to assess all individuals who self-injury. Based on the evaluation results, the following options may be considered:

- No treatment/follow-up.

- Psychological treatment, typically of a cognitive-behavioral nature.

- Psychiatric treatment with medication: while there is no specific medication for self-injury, medications can be highly effective in addressing underlying conditions like anxiety and depression.

Briefly, self-injury is a growing problem that often begins in early adolescence and, in a notable percentage of cases, persists into adulthood. It is driven by feelings of distress with the aim of emotional regulation, posing a risk of becoming addictive and replacing other, more adaptive coping strategies. It is also essential not to overlook this issue due to its association with suicide attempts.

If this applies to you or someone you know, remember that we at Sinews are here to help.

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

All about SSRI antidepressants (practically)

“I found out what happiness is only after taking sertraline”.

“Before starting paroxetine, I had panic attacks every single day, getting out of my house was a big no for me”.

“Escitalopram has made me improve till being able to participate actively in my psychoterapy”.

These sentences, and many others that we psychiatrists hear in the office in Madrid quite often underline the value of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), the antidepressant medications most prescribed currently although, as we’ll discuss later, they are not only used for depression.

These are the SSRI, in order of development:

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox).

- Fluoxetine (Prozac).

- Citalopram (Celexa).

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat).

- Sertraline (Zoloft).

- Escitalopram (Lexapro).

And their approved indications:

- Depression.

- Generalized anxiety disorder.

- Social anxiety disorder.

- Panic disorder.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Postraumatic stress disorder.

The first ones started to be used at the end of the 80s, fluoxetine particularly, and became so famous that a few years later we could read best-sellers whose title contained the word “Prozac”, brand name for fluoxetine: Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America (E. Wurtzel, 1994), Amor, curiosidad, Prozac y dudas (Love, curiosity, Prozac and doubts; L. Etxebarría, 1997), Plato, not Prozac! (L. Marinoff, 1999), or even El Prozac de Séneca (Seneca’s Prozac, C. Newman, 2014).

These medicines put in the public arena much needed conversations about mental health, and have contributed hugely to lessen the associated stigma: they brought along a great revolution in the treatment of various disorder and in closing the gap between Psychiatry and global society.

In order to understand why SSRI meant such a revolution we have to consider the psychopharmacology then present, used to treat depression and anxiety: the “old” antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOI], tricyclics) and barbiturate/benzodiazepines. Even though they are really effective, their side effects cause discomfort to say the least, most are sedating, may be lethal in overdose and their addiction potential is high. With SSRI, for the first time ever the psychiatrists have at hand a pharmacological armamentarium which is effective, well tolerated, easy to dose and not addictive.

The name betrays their mechanism of action: these drugs inhibit in brain synapses (sites of communication between neurons) the reuptake (return to the cell) of serotonin, a very important neurotransmitter; this leads to an increase of available serotonin in the synapsis, and gave rise to the «chemical imbalance» so widely purported for years as cause of the symptoms: both patients and doctors claimed that a “deficit of serotonin” lay at the root of the disorders. This excessively simplistic notion has been discarded (among other reasons, because the increase in serotonin in the synapses occurs immediately, while the antidepressant, antiobsessive or antianxiety action usually takes from days to weeks) and currently we consider that these medications act instead as “emotional regulators”, modifying emotional perceptions at unconscious level. It is clear that serotonin is just a piece in the big brain puzzle and mental disorders, but the fact that we ignore the exact mechanism of action for SSRI does not necessarily mean that we shouldn’t use them, as some claim. Suffice to say that we still don’t understand the mechanism of acetaminophen (paracetamol), one of the most used medications in the world, and we don’t let this stop us from making use of its great efficacy to treat the headache or fever caused by a cold, for instance.

What is it like to take antidepressants (SSRI)

And after this theorical discussion of their mechanism, here comes a more practical exposition. ISRS are extremely easy to take: once a day, with or without food. They are very safe (even in pregnancy!), have very few absolute contraindications and are mostly very well tolerated. Their most frequent side effects are upset stomach and nausea (up to 10%; they usually disappear after a few days of treatment), excessive sweating, nervousness (they may increase anxiety initially) and tremors. Other effects, much less frequent (1% maximum) include sexual issues (from decrease in libido to impotence and lack of orgasm), a feeling of excessive emotional indifference, suicidal ideation and bruising/bleeding tendency. We must remember that most patients do not suffer any effect, the vast majority of them tend to disappear as the treatment goes along and very often it’s possible to minimize them starting with low doses and increasing as suggested by the 2017 top song: des-pa-ci-to (slowly, just in case there’s still someone unable to translate).

It is always appropriate to remind that, as it is the case with every other medication in continuous use, they have to be recommended, prescribed, controlled and withdrawn by a doctor: let us help you here at SINEWS, with SSRI and a lot else!

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

What is chronic pain and how can it be managed?

Even though I am a psychiatrist, the lines and paragraphs that follow aren’t devoted to moral or soul pain, that pain no Band-Aids will ever cure, but “organic” or physical pain, where painkillers are so efficient (aren’t they?).

What exactly is pain?

Pain is a defensive mechanism. So boldly stated, it might be viewed even as an insult to all those doomed to live in pain on a daily basis, but a little reflection is enough to realize why evolution has promoted its existence. Pain is the very first “red flag”, a signal that something is wrong and compels us to acknowledge it: either stop moving a painful limb, which may be fractured, or seek immediate help with the unbearable pain of a heart attack. The rare people who cannot feel pain due to a genetic deficit are witness to those benefits, as well as the ailments, much more frequent, that patients with diabetes suffer in their feet because the damage of the nerves that transmit the pain makes them unable to feel it, so a simple graze due to tight shoes may become a terrible ulcer as these people lack this warning system whose function is to alert us of potential dangers.

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines acute pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with actual or potential tissue damage. This definition states something we all know, but it is so difficult to convey to other people, or even to acknowledge its severity. The best tool to quantify pain, the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), asks us to score our pain from 0 to 10. This provides an easy way to assess the efficacy of a treatment for pain, calculating the percentage of decrease in VAS.

Which types of pain can we find?

The simplest classification is acute (defined above) and chronic:

- Chronic pain, as opposed to acute pain, is a persistent pain state not associated with the triggering event and exists beyond the normal healing; it lacks a protective role.

- Acute pain is usually a symptom of the underlying health problem, whereas chronic pain is a disease condition in itself, with symptoms of refractory pain, functional and psychological impairment, and disability.

Another important distinction is between nociceptive pain, due to the activation of pain receptors or nociceptors, and neuropathic, secondary to the disturbance of the very same nervous structures committed to the transmission and perception of pain. Nociceptive pain is what we feel with a hit, puncture, heat, inflammation, etc., while neuropathic pain is felt more as an intense “bolt”, an extremely unpleasant sensation difficult to describe: the best-known example is the shock we feel along the forearm when we hit the internal aspect or our elbow. It is also usually accompanied by changes such as dysesthesias (distorted sensations: burning, tingling), hyperesthesia (oversensitiveness) and allodynia (pain perceived with painless stimuli).

How is pain transmitted?

We have a good knowledge of pain transmission paths and the substances involved. Concisely and simply put, the sensation starts at the nociceptors, specialized nervous structures, and from these to sensitive nerves, spinal cord, thalamus and eventually several brain areas, ultimately responsible for the perception of pain.

This deep knowledge of structures and substances permits on the hand to understand how pain is the result of damage to the various levels (spinal cord injury, stroke) and, on the other, develop strategies to fight pain in every front (blocks of peripheral nerves, spinal stimulators).

How is acute pain managed?

It was several decades ago (1986) that the World Health Organization (WHO) released its “pain relief ladder”, initially proposed for cancer pain and adopted subsequently in other conditions. The pain is graded in mild, moderate and severe (according to the VAS score) and suggests various medications in each of the steps, from acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID: ibuprofen, aspirin…) to the strongest opioids (morphine, fentanyl) in the last one.

Generally and even though there are obvious exceptions, the management of acute pain with medications (through several routes: oral, intravenous, regional, epidural…) obtains an effective relief. It is important to adjust carefully the doses and duration of the treatment to avoid complications and specially, addictions to opioids.

What is the way to chronic pain?

With repeated and ongoing exposure to painful stimuli, our central and peripheral nervous systems undergo a process known as sensitization, dependent upon neuronal plasticity: the final result is persistent pathological pain: enhanced and prolonged pain perception after minor nociceptive stimuli, or even in absence of these. Once peripheral and central sensitization are involved, the pain is usually more difficult to treat or even refractory to standard therapies.

It is now believed that this sensitization process is involved in a wide variety of chronic pain conditions, such as tension headache or carpal tunnel syndrome, also in those previously thought to be mainly nociceptive in nature (osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia).

What are the most common causes of chronic pain?

The most common causes span from primary pain disorders (fibromyalgia, chronic headache) to rheumatological (arthritis), endocrine (diabetes) and orthopedic (disk hernia) conditions: all of them are prevalent disorders in general population. Even though the various reports yield widely variable figures, the lowest estimate of prevalence for chronic pain in general population is around 25%.

How is chronic pain managed?

In chronic pain, which constitutes a disease entity by itself as we stated above, medications are just a small part of the management. The best outcomes come from a multimodal approach, consisting on the simultaneous, instead of sequential use of multiple treatment modalities for pain: medicines (not only painkillers, certain antidepressants and antiepileptics are first line treatments in several pain conditions), rehabilitation (physical therapy, occupational therapy), psychology (see below), interventional pain management (peripheral nerves block, epidural injections), implantable devices (spinal cord stimulators, intrathecal pumps), complementary and alternative medicine (acupuncture), nutritional counselling (losing weight), vocational counselling (return to work).

It is essential to identify and treat all the comorbid conditions if we aim to have good outcomes in chronic pain, including psychological/psychiatric disorders or even the lack of social support.

What is the role of psychology/psychiatry in chronic pain?

Many of the people who suffer chronic pain also have psychological/psychiatric disorders, mainly anxiety and depression; it is not pure chance that every Pain Unit is staffed with a psychologist/psychiatrist.

Just like those philosophical questions so difficult to answer, it remains a challenge to differentiate between cause and effect, whether anxiety and depression came before the pain or this is the root cause of the psychological issues. Anyway, it seems reasonable to assess and treat the actual condition, and worry later, almost at a mere academic level, about establishing which one arrived first.

Antidepressant drugs treat anxiety and depression, and one of their categories, the so-called “dual antidepressants”, which enhance both serotonin and noradrenaline, is the first-line choice for neuropathic pain.

There are multiples modalities of psychotherapy well described in pain: hypnosis and visualization, guided imagery, biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, group psychotherapy and family therapy. They use different techniques, but all of them have in common assisting the patient to cope with the condition and avoiding pain from becoming the absolute focus of their lives.

A message of hope: the advances in the understanding of paths and substances involved in pain, recent developments in its management, from new pharmacological strategies to outstanding interventionist procedures, together with the realization that psychological/psychiatric therapy constitutes an essential component of a comprehensive management of pain, have permitted and will further permit that many people won’t be doomed to live in pain anymore.

About the author

Alicia Fraile is a psychiatrist at SINEWS with more than 20 years of experience in general clinical psychiatry. She has worked in brain damage, Mental Health Centers, occupational psychiatry, work accidents and their repercussion in psychiatry (post-traumatic stress disorder, adaptive disorders), patients with chronic health problems and of course with the most frequent pictures of our field: anxiety, depression, insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder.